It was time for her to take center stage.

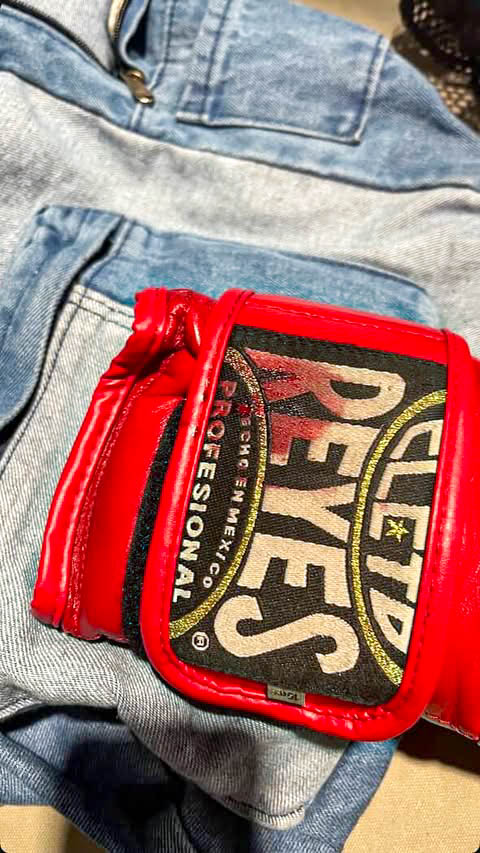

Her character shoes, used for dancing, glide and stomp on the Red Lion Tavern wooden stage. Her traditional Romani dress makes swift but elegant motions around her.

At the Texas Renaissance Festival, junior Dasha Mangupli gets to do what feels “comfortable.” She gets to dance with the girls who know her movements, her language and her origins.

“When I dance, I feel the closest to my culture,” Mangupli said. “I’m not thinking about something I have to do or homework I haven’t done, I just dance.”

Twenty six years ago, Mangupli’s parents immigrated from Kazakhstan, a country just below Russia. For Kazakhs, the United States is a place of opportunity; it’s considered “the dream.”

When Mangupli was 12, her parents divorced. Her father advocated for him and Mangupli’s mother to leave for America.

Now, it is just Mangupli, her two older brothers and her mom at home. After school, Mangupli speaks Russian to her mother and finds a sense of comfort in speaking her native tongue.

“School is always heavy on homework, anxiety and stress for me,” Mangupli said. “But whenever I’m at home, since I’m not even speaking English anymore, it’s kind of like I forget about it.”

Dancing has taken on a similar role for Mangupli. When she was five years old, Mangupli’s mother, Marina Mangupli, was told about a hidden dance studio behind a Russian general shop in their neighborhood, a Russian enclave centered around the neighborhood of Meyerland. Although Mangupli’s family is Khasakstainian, their primary language is Russian due to the geographical proximity. Because of this, Mangupli is “heavily connected” to Russian culture.

“Russian communities are tight,” Mangupli said. “Since we’re not in a country where everyone speaks Russian, if you hear something, it’s going to get around.”

Marina, in fact, learned of this dance studio from a co-worker. He knew of the studio’s dance instructor and got Mangupli into dance classes.

“She loved it a lot and went to class happily every time,” Marina said. “That’s where she learned a lot of her Russian culture from the start.”

Marina wanted to make understanding Mangupli’s Russian side a priority for Mangupli since she would become accustomed to the American lifestyle through school. She has found raising her kids in a primarily Russian area beneficial for Mangupli.

“I see all of these people as my own, my close people that can fully understand me,” Marina said. “We don’t need to prove ourselves or help others understand us because everyone’s already connected in a way.”

The dance studio’s group, Uzori, was a consistent source of connection with her background until Mangupli was around 10 years old.

“It got more intense, and my [dance instructor] started putting me in the center,” Mangupli said. “When I was a kid, I was shy, and I didn’t like that. My mom understood and didn’t want to make me uncomfortable, so I took a break.”

The COVID-19 pandemic began one year later, extending her short break to three years. At that point, Mangupli didn’t think she was ever going to go back to dance. She enjoyed it, but the performance anxiety took over the enjoyment.

“The break was longer than anticipated for everyone,” Mangupli said. “Once Covid had faded out, my instructor said ‘Let’s get it back together and see if people are down to come back.’”

The dancers had a hard time coming back together fully, as they were not constant with attending rehearsals. But for Mangupli, this space filled with her own identity and origins had a sense of consistency.

“Getting back with this group of girls, kind of overpowered my old issues with anxiety on stage,” Mangupli said. “I was focused on finding my people again after COVID.”

This reestablished dance group didn’t last long due to a lack of commitment from the dance instructor as well as the dancers in attending the Saturday rehearsals.

It wasn’t until 20-year-old Sasha Dovzak, one of the dancers in the group realized it was in her hands to bring the girls together again.

“After the original troupe sort of died out, mostly because our director stopped having rehearsals, the girls, one of them being my sister, kept mentioning how much they missed dancing,” Dovzak said. “I realized [that] if I wanted to dance with them again, I had to do something about it.”

Dovzak put together casual practices hosted between her own apartment complex and a studio where she taught belly dancing. It was at these practices where the Texas Renaissance Festival was mentioned by one of the dancers. Dovzak saw this as an opportunity to showcase her love for Gypsy dancing, which played a big role in why she established a new dance group.

“The Gypsy dance genre has been my favorite style my entire life,” Dovzak said. “I had so many ideas for choreography [and I] had tons of music and costumes to pull from. I didn’t know where or how we could perform, but I did know that I could put together a group and we [could] start there.

And she did. With Mangupli being one of the main dancers and part of Dovzak’s leadership team from the beginning, these girls were able to make performing with the Renaissance happen, following Dovzak’s Romani dancing vision.

The first step was the audition process hosted at Todd Mission, where the festival takes place. This experience was foreign and nerve racking for Mangupli.

“Almost all of the people there knew each other, they all come every year to show what they have come up with,” Mangupli said. “We didn’t really know anyone there, so we were just waiting, all dressed up, and very nervous.”

The girls were then called into the audition room. Originally, there were supposed to be four judges at the front of the stage, but one judge invited the other auditioning acts to watch Mangupli’s group audition.

“It definitely made [the nerves] a lot worse,” Mangupli said. “At this time, I still wasn’t fully comfortable performing in front of people confidently, and you could see it in the way I presented myself on stage.”

After the audition, Mangupli said that people in the audience actually helped with the energy in the room, as they would follow Dovzak’s instructions as the group Emcee to clap and holler for the dancers.

“Once it was over, I felt really good, like I finally did it,” Mangupli said.

Around three months after the audition, the girls got news that they would get to perform at the festival, starting in October 2024. The exciting news was followed by extensive prep from Mangupli, Dovzak and all dancers.

“I had to put together a forty minute show that wouldn’t be boring or repetitive,” Dovzak said. “We had about three months to put together and clean eight numbers and each solo.”

This opportunity was valuable for Mangupli because of the memories that the Renaissance Festival provided her as a child.

“The Ren Fair was something I had gone to since I was a kid,” Mangupli said. “I would go every year with my family, and now instead of being the one clapping in the audience, I’ll be the one to clap for.”

Mangupli would drive herself 50 miles north of Houston every Saturday to perform. When she arrived, Mangupli squeezed through a hidden alleyway between gift shops and food stands that would lead to a small shack filled to the brim with makeup, skirts, curling irons, corsets or anything a Gypsy dancer would need on stage.

Inside the shack, she speaks Russian and English interchangeably. Small talk about the order of the solos for that show, which costume each dancer would be wearing that day and the new earned back pain from the constant performing and rehearsing.

Though the style at the Renaissance Festival isn’t Russian Folk Dancing, she still carries the nostalgia of being with the girls who know that part of her.

“Now that I’m home less and less, that switch to fluent Russian doesn’t happen a lot anymore,” Mangupli said. “So whenever I dance, it’s only focused on [my culture], with no other distractions.”

Being a senior next year, Mangupli is still deciding whether she will continue dancing in honor of her culture.

“If I find a [dance] group where I end up going to college, I’ll for sure join it,” Mangupli said.

Though she gives credit to her mother for introducing her to the world of dance, Mangupli has made it her own. Despite the anxiety of performing and the inconsistency of her original studio, Mangupli is driven by her pride for where her origins lie.

“It has always been part of my life, something that has always brought up my Russian culture,” Mangupli said. “I am proud of that.”

For Marina, it has been a privilege watching Mangupli grow up, honoring her culture through dance.

“At the start of her dancing, she would always look at others to confirm that her movements were right, not being confident,” Marina said. “I loved seeing her grow into it, where instead of looking at others she would look at the crowd, and see how the crowd would look back at her.”

Ellie Zacharia • May 28, 2025 at 10:37 pm

such an amazing story camila! my best friend writing a story on my best friend 🙂