Uprooted: New student compares life in South Korea to America

Photo provided by Zachary Johnson

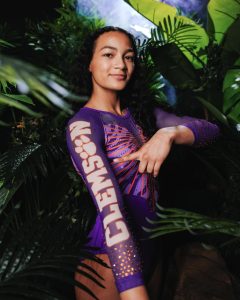

Zachery (far right) celebrates with friends Valeriya, Maddy and Amelia near the Han River. This was their last day of school so they took this time to explore Seoul.

Jan 13, 2021

He didn’t see his dad for a year. Another time his dad left without warning. That was the first time he missed his dad. After that, it was just normal.

Sophomore Zachary Johnson’s dad was a one-star general who was deployed to Seoul, South Korea in 2018. He left for up to two weeks every month before that for work reasons, but this time, he wasn’t the only one going. Originally, Johnson, his mom and his youngest brother only planned to visit for a week. But a week turned into a month. A month turned into two months.

Two months turned into two years.

“I slowly got used to the thought that we were going to move there, so it wasn’t a big shock or anything, but I didn’t get to say bye to anybody because I thought I was going to be back,” Johnson said, who lived in Korea from June 2018 to June 2019.

Johnson said he never really got close with his American middle school friends, but he met many of his best friends in Korea and found a new sense of freedom.

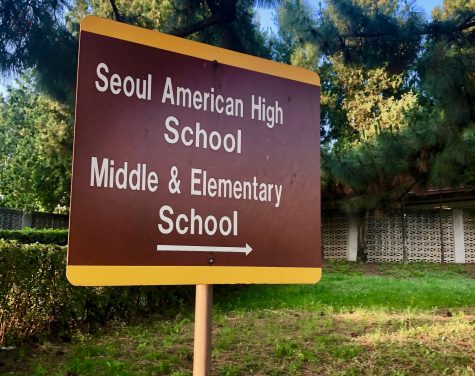

For the two years Johnson’s family lived in South Korea, they lived in a military base home. The school he attended was filled with kids from all over the world who were also related to officials. The school, Seoul American Middle High School – which has since closed – was small, with around 200 kids in middle school and high school combined, but Johnson settled in just fine.

“On the first day of school, I remembered a girl from a couple of weeks earlier in orientation.” Johnson said. “I was like ‘I’m gonna go say hi to her and sit next to her so I don’t look like a loner.’ So I said ‘hi’ to Savannah, and she was with her friend Avery who really became my best friend, later on.”

During the first month of classes, Johnson clung to these two friends, but started to get closest with Avery. Every morning, he would walk down a steep mountain to meet with her at the nearby Starbucks as they walked to school in the pitch-black Korean cold.

“Avery and I were really close, but I made lots of friends while I was there,” Johnson said. “At the end of the school year, we had a closing ceremony, and I was nominated by my classmates to ring the closing gong. I wore a suit and everything.”

Although Johnson loved the school and the people there, he mentioned a sense of tension in everyday teachings. Along one wall of the room there was a line of gas masks, a constant reminder of possible threats from just up north.

“We had military drills,” Johnson said. “If a bomb were to go off, like if a bomb were to be coming towards us in seconds, we had a safe place.”

Located behind a bookcase in the school, the safe place, which needed an entrance code, led down to a concrete room lined with food, hazmat suits and other needs for survival.

“If an atomic or nuclear bomb were coming towards us, well, we may die. But if we did survive, that’s where we are. It’s pretty scary,” Johnson said.

In spite of monthly drills and the looming presence of threat, Johnson managed to be comforted by a newfound freedom.

“One of the first things I noticed in Korea was how conforming America was.” Johnson said. “Like, I had to wear a uniform and I had to do this, do that. But when I got to Korea, it was so new. I had tons of friends and we would just explore places. I could wear whatever I wanted. It was really fun. It was like a new beginning. I just had so much freedom in Korea”

With this new freedom, Johnson mentioned how much he felt he could change. He began listening to new artists like Conan Gray and watched new shows like Lady Bird, which helped him gain new interest in painting and fashion.

“I never really explored fashion until I got to Korea,” Johnson said. “It’s when I started wearing my own stuff. Korea is very fashion-forward, almost futuristic, which helped me out even more. But besides clothing, I think I changed a lot. I just saw things in a different perspective than I did here in Houston. I realized, ‘wow, everybody really is the same.’ But everybody has their own thing.”

Johnson’s mother, Demetria, also took note of changes in her son.

“I noticed a change in Zachary as Korea allowed him to grow up and spread his wings,” his mother said. “He enjoyed his flexibility in choices and not being contingent on ours.”

Although one of his biggest fears was to leave his unique life behind, the day of his departure from Korea, June 2019, Johnson said he did not feel as much as he thought he would.

“I didn’t cry or anything. It was just like ‘Oh, we’re going back to America,’“ Johnson said. “I guess I was a bit upset, but I realized something while living halfway across the world. I just realized that I was born in America, and there’s no other place that I’d really be accepted into, you know?”

Johnson loved the idea of living in another country, but there were so many things that separated him from the local residents, such as his culture, his ideas and even his skin.

“I never really saw it as a form of racism,” Johnson said. “It’s just that some people had literally never seen Black people before. They tend to be more handsy in Korea. It’s just natural there, so strangers would touch our skin sometimes. Some people liked it, others didn’t, but many just seemed fascinated by it.”

On the morning of June 23, 2019, Johnson packed his bags, but not for the plane ride home, for his last day of school. Many of his friends would also be departing Seoul because of their parents’ new job opportunities, so it was likely Johnson would not see them in person for a very long time.

“Me and my friends were like, ‘You know, we should just go everywhere in the city in our last six hours,’” Johnson said. “So literally, on the last day, we went to Seoul Tower and then the aquarium. We went to the Han River. We walked to the food trucks. We literally moved on the last day of school and I guess that was our parting. That was the last time I saw them.”

Eighteen long hours later, Johnson and his family arrived in San Antonio where the four of them lived until August of 2020.

“I didn’t like San Antonio,” Johnson said. “Neither did my family. I missed the freedom I had in Korea. My parents were still lenient in America, but there’s not really anywhere to go here. It was just so empty. It was monogamous. It was so basic. In America, you do the same things all the time. It’s so repetitive, and you don’t really realize it. In Korea, it was such a big city that you could do something new every single day. I guess Houston is the same, but there’s definitely more culture here than San Antonio.”

Johnson was excited to move back to his hometown of Houston on June 20, 2020. There he would get to reunite with old friends while starting new classes here at Bellaire High School.

“Don’t get me wrong, I love Houston,” Johnson said. “I just lost a lot when I moved back here, like things that I used to do. It’s just not the same in America. I miss the small things like morning train rides and distinctive food.”