‘I couldn’t sing, dance or wear bright colors’

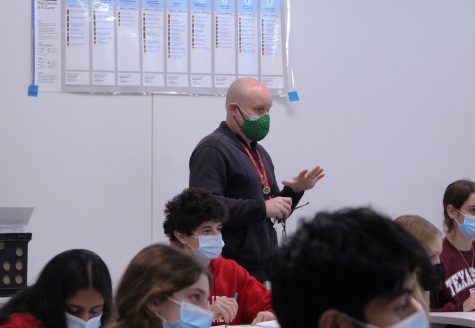

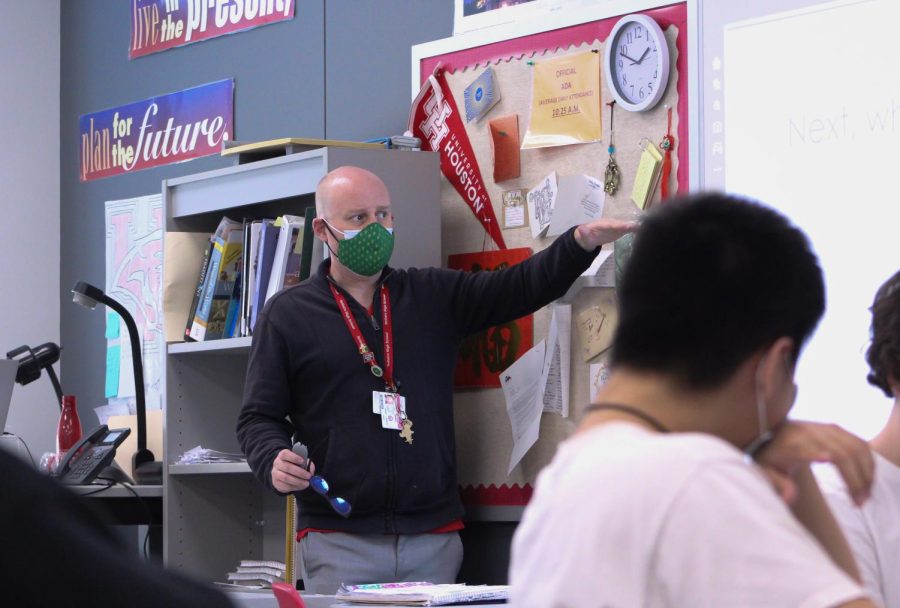

Justin Cothran introduces a new concept to his AP World History Class during 5th period. Change and Continuity Over Time is a skill that students must master in order to be prepared for their exams in May.

Not long after we sit down in his classroom amid the buzz of students, he admits that he still hears his parents’ voice in his head.

“Wear muted colors.”

“No music.”

“Don’t indulge.”

As a child his parents would drill these rules into his head.

Justin David Cothran, AP World History teacher, is a self-described “bad Calvinist.” Growing up in the 80s and 90s, Cothran lived in an ultra-religious Calvinist household. His father was a Calvinist minister, so the church followed him wherever he went. They were conservative, even by Calvinist standards.

Calvinism was a religion born out of the Protestant Reformation. It was a particular type of Protestantism that was a direct reaction to the Catholic Church. It was also a direct reaction against the indulgences of the Catholic Church.

According to the tenets of Calvinism, Cothran is a member of The Elect, selected by God. However, this is a point that Cothran is not spiritually sure of.

“It’s hard to explain,” Cothran said. “Even I don’t quite understand it.”

Cothran went on to explain that the Calvinist concept of predestination is very difficult to explain to non-believers. Even Calvinists disagree on certain aspects of predestination.

A central part of Calvinism is isolation from society, which heavily shaped Cothran’s upbringing.

“It wasn’t a pleasant childhood,” Cothran admits. “We really stuck out.”

As a Calvinist, Cothran could not watch movies, dance or attend mass socializations. He also had restrictions on dress, such as no flashy colors and long sleeved outfits with minimal skin.

“My mom regulated what I wore and checked [my outfit] before I left the house,” Cothran said. “You didn’t show your body in public.”

Despite quitting Calvinism, the dress constraints are still ingrained in him.

“You’ll notice I always wear long sleeves because I was not allowed to wear short sleeves,” Cothran said. “I rarely if ever wear short sleeve shirts and shorts [as well].”

Strict dress codes aren’t the only things ingrained in Cothran; he also avoids overindulging on sugar.

“We were only allowed to have sugar every once in a while, ” Cothran said. “I eat way less sugar than the average American.”

The topic of Calvinism remains sensitive for Cothran.

“You’re privileged here because I don’t normally talk about this with anyone,” Cothran said.

Growing up in the primarily Southern Baptist central Texas countryside, Cothran was interrogated by his school teachers over his Calvinist faith. He was also teased by schoolmates for his religion.

“People have a natural fear and tendency to mock what they don’t understand,” Cothran said. “So very early on I knew that I was different.”

Cothran left Calvinism a little after college at age 27. Throughout college, he studied history more in-depth and realized Calvinism didn’t make him happy.

When we pointed out the hypocrisy of giving up Calvinism when a central tenet of the religion is never giving up, Cothran admits that it’s a fair point.

“I have consulted church officials and it’s [a choice] that I can live with,” Cothran said. “Because ultimately, I believe that the relationship with God is personal and I made the decision that Calvinism and me are not a healthy mix.”

While the break away from Calvinism gave Cothran more freedom, it led to a break with his family.

“It caused a serious rift between my dad,” Cothran said. “I’m sorry to say there was a two year period where we did not communicate.”

Despite quitting Calvinism, Cothran says that he is still a deeply religious person.

“Not to be cute, but I’m a recovering Calvinist,” Cothran said. “The religion I most identify with is Eastern Orthodoxy [but] to be honest, I still investigate religions.”

It wasn’t all bad though, since Cothran thinks it gave him thick skin. Wayne Houle, history teacher (and possible best friend), notices Cothran’s strength.

“He’s a tough guy,” Houle said. “He stands up to authority if he has to.”

His students also describe Cothran as a hardworking and strong person.

“He always enters grades as soon as he can, sometimes on the same day,” sophomore Sara Rozen said.

Cothran’s diligence towards teaching has led him to be department chair and team lead of Bellaire’s history department. For Cothran, the work he’s done at Bellaire is something he’s proud of.

“I’m part of one of the most successful AP World teams in the state in terms of public high school,” Cothran said.

For Cothran, he sticks by religion because it makes him a better person.

“We can’t just slap a justification on our faults; we’re supposed to work on them as we go along, ” Cothran said. “That was oddly something about Calvinism that I like [since it] requires you to work on yourself.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Bellaire High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

McKenzie Le • Nov 2, 2023 at 8:47 pm

I just came across this story right after Mr. Cothran mentioned it in class. This is such an interesting story.

Abigail • Mar 1, 2022 at 9:45 pm

this story is cool. mr. cothran is awesome

Addi Senfulu • Mar 1, 2022 at 6:37 pm

MY FAVORITE TEACHER!!!!!! GO MR. COTHRAN!! SO PROUD OF YOU FOR SHARING YOUR STORY!!!

Allenya Mooroir • Mar 1, 2022 at 2:36 pm

As a woman of the First Cumberland Presbyterian Church. I was shocked to learn Calvinist’s beliefs/views on God’s love. It is so subjective and leads non-Calvinists(such as myself) to feel jealous that I was not “chosen” by God to be a part of this religion. I really appreciate this story that sheds light on Calvinism and how different it is from other religions.

kyle kaylen • Mar 1, 2022 at 2:27 pm

Yassss queen!! SLAY!! SO HAPPY FOR YOU MR. COTHRAN

Annie Greenhill • Mar 1, 2022 at 2:25 pm

I love Calvinism. I actually study it as a profession. Such an interesting religion. It’s crazy to hear that someone has experienced that lifestyle.