Under the sea: The mechanics of aquarium maintenance in aquatic science explained

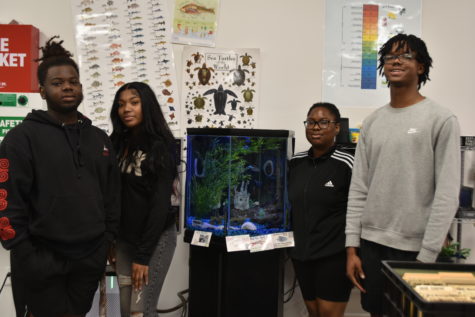

Group member of “The Majestics” and senior Chloe Saunders regularly analyzes her aquarium’s health in aquatic science teacher Stephanie Clayton’s sixth period, room 2730. A fun fact about “The Majestics'” angelfish is its compatibility to coexist with gourami fish.

When students step into rooms 2728 and 2730, drawing tools, scissors and Elmer’s glue aren’t the only supplies to complete the classrooms. Instead, a different arsenal adorns the spaces: aquariums.

Lined across the black countertops, fish and turtle aquariums, decorated with hand-painted and laminated construction paper backgrounds, crowd the perimeter of the classrooms.

Other organisms housed include eels, seahorses, starfish and an axolotl.

Illuminated with lights and embellished with waterproof decor, the miniature aquariums imitate vibrantly-hued reefs in crystal blue oceans.

Welcome to aquatic science, a senior-specific elective that covers curricula interactively.

Instead of pumping out worksheets every day, aquatic science teachers Stephanie Clayton and Jane Baker assign group work, energizing students to work collaboratively.

Announcing the layout for each day’s work, students may be asked to color code different marine organisms based on their organs and list their functions, take notes on documentaries discussing abused, captive mammals or lead a series of labs.

Students read and highlight paragraphs of various species, kingdoms, classes, families and genuses organisms fall under.

Throughout the school year, students dissect squid, crawfish, crab, starfish, occasionally a clam or oyster and the cherry-topping shark.

Hearing students would be looking after fish in aquariums surprised Chloe Saunders.

Making up one-third of her group “The Majestics,” taking care of aquariums took Saunders aback.

“I didn’t know [the teacher] would trust us enough with fish,” Saunders said.

Saunders didn’t choose aquatic science, but she felt the course chose her.

Originally enrolled in AP Chemistry, the class already reached full capacity, so Saunders’ counselor Angela Davis registered her into Clayton’s sixth period.

When Clayton explained the class’s expectations, she casually mentioned tending to aquariums. This soon became the highlight of Saunders’ school day once she got the hang of the routine as she now cares for an angelfish and gourami.

Tank maintenance happens once a week on any day, but Clayton and Baker expect groups to loosely check all parameters daily. If students finish their classwork early, they walk to their aquariums and briefly analyze that their fish are healthy looking and the interior appears clean.

Given a fill-out sheet, groups cite the data for tank upkeep. The first criterion to check off the list is “Water.” Students examine the water’s color, clarity and odor. Healthy appearing water is clear and lacks smell.

One of Clayton’s second period groups “AQUA4OUR” regularly manages to keep their water at peak clarity.

Group members of “AQUA4OUR” Jaevia Shivers and Timothy Addison came up with the group name.

“We’re dealing with aquatics, so “AQUA,” and there are “4” members in our group,” Shivers said.

Writing down “Clear” every day of tank maintenance, “AQUA4OUR” also writes confident updates for the remaining categories upon inspection.

A division of labor between Shivers, Addison, Chelsea Lambert and Matthan Jones helps to cover the tasks in 15 minutes or less.

“Matthan puts the tube into the tank to take out the water because he’s the tallest, Tim stirs the [gravel], Jaevia puts back the decorations in the tank and I dump the old water and put in the new water,” Lambert said.

The second step to examine is “Detritus.” Algae, uneaten food, brown bottom fuzzies, body parts, floaters, color changes in decor, wood and more fall under this category.

Too much light exposure, infrequent water changes, or if the heater is cranked up too high all cause algae overgrowth in aquariums. Students combat fuzzies by brushing the interior or using a paper towel to wipe it down. Windex or Lysol keeps the exterior glass spotless.

Next, Clayton and Baker provide pH test strips to dip in the water for about a minute. Freshwater aquariums should sustain a pH level between 6.6-7.8 while saltwater aquariums, 7.8-8.5. Accumulated waste due to overfeeding fluctuates pH and nitrate levels.

Then, peers record “Temp”. Freshwater is estimated to be 77-83 degrees Celsius, while healthy salty water fits the 76-82 degrees Celsius range.

After, students use a nitrate reader where a 5-10 ppm measure of nitrates in both fresh and salty water is “tolerable.” Vernier supplies the Nitrate Ion-Selective Electrode to Clayton and Baker for free. Nitrates are ammonia that fish release in the form of their waste. If that builds up, it can intoxicate the water.

The sixth step is reserved for “Significant Events.” Groups document new changes or anything irregular occurring in their tank.

Examples of these include new organisms, deaths, new decorations, cloudy water, sick fish, malfunctioning equipment, unusual behavior, wavering coloration, spots, slimy strings, rapid breathing of fish, hostility, missing fins, red lines — indicating stress or inflammation — and other physiological warning signs.

Groups always document chemicals added with the quantities indicated, swapping out and rinsing filter pads, as well as water changes.

Every Monday, students take a tube and siphon out approximately 10-20% of tank water in a bucket and dump it in a nearby sink. They then fill up fresh water from the sink into the bucket and mix a 1/10 mL of water conditioner, an odorous solution used to remove chlorine.

“H2O Level” follows next on the checklist. Groups have to make sure their vertical water line isn’t visible and fuel the tank with more water if that’s the case. The water line decreases due to evaporation.

“AQAU4OUR” feeds their silver killifish, red tail shark fish and “unknown” beta fish — which its family and genus are are still in question — a pinch of food every other day.

Before class is dismissed, students turn off all of the aquariums’ lights within their proximity.

For everyone’s first batch of fish, peers walked a little way to an overpass to catch ditch fish swimming in shallow, muddy water below, then acclimation followed.

Acclimating fish means familiarizing those newly caught or purchased fish with their new home. The fish come in plastic baggies where they are plunged in tank water for 15 minutes and secured by a clip. Then students pour half a cup of tank water into the baggy and wait an additional 15 minutes before transporting the fish into its new home.

Acclimating their second batch of fish, Shivers’ preference slighted toward one fish in particular.

“My favorite fish is the “unknown” beta fish because it has different shades of blue and blue is a brightening color,” Shivers said.

Addison shared the same propensity for different reasons.

“The color of the fish changed since it’s been in the water, and we don’t know the reason why it changed since it’s an unknown fish, so it’s really the curiosity behind it,” Addison said.

Until six years ago, tank maintenance for all students didn’t exist in the Aquatic Science Department except for several of them scattered across the classroom for aesthetics.

When Baker took the department overboard, she realized aquatic science implemented more paperwork rather than focusing on aquariums.

Rounding up her seventh year of teaching at Bellaire, Baker also taught aquatic science at Brazoswood High School then served as an education specialist at Space Center Houston where she helped organize science camps for 10 to 12-year-olds.

Baker and Clayton come from museum backgrounds, teaching at the Houston Museum of Natural Science for seven years, 20 years ago.

They taught field camps, one of them being coastal ecology where children went on field trips, one being an overnight beach stay.

The pair then learned what they absorbed during their time there and brought it to their classes after Baker invited Clayton to teach beside her.

The two reunited and birthed their tank management system, but with the birth of the aquariums came fish deaths.

Groups start out with trial or ditch fish, which consist of the majority of fish fatalities.

“It’s the circle of life,” Baker said. “We always use free stuff at first, then second semester [students] are more capable and understand water quality. Then we buy [more species of fish] as a reward because students know what they’re doing now.”

Saunders’ group supported two ditch fish for a few weeks.

One of them, Nemo, died.

“I was devastated,” Saunders said. “We picked out a name for him and everything.”

Taking advantage of the resources available, such as the ditch, is imperative. Aquariums are expensive.

Allowing kids to maintain aquariums requires monetary flexibility, which forces Baker and Clayton to often squeeze out solutions.

The department receives no budget relief from Bellaire. Money comes from $20 lab fees charged to each student, donations and applying for PTO grants.

Clayton goes the extra mile, advertising on Facebook marketplaces.

I’m like, ‘Hey, do you have any aquariums in your garage you don’t want?,’” Clayton said. “My husband and I went around and picked up a bunch that was all over town. My husband built stands for tanks.”

Even with the financial struggles, Clayton and Baker still want students to enroll. They campaign aquarium culture by exposing underclassmen in hopes of even more registrants when a fresh pool of seniors tides over.

Setting up aquariums in classrooms, English teacher Elizabeth Chapman (Room 2712), Grad Lab Coach Joseph Ogle (Room 1510) and special ed teacher James Upton (Room 1151) all hold aquariums. Clayton and Baker piloted the idea of different student groups managing their aquariums in other classrooms to attract particular audiences.

This method adds flavor to credit recovery and offers a calming experience for the special ed kids where they can have something to watch, as well as feed the fish.

When assigned artsy projects and dissections, groups post their finished products on Instagram, tagging their teachers and Bellaire to further expose the content of the class.

Overall, it’s a special class for the students and teachers and should be treated with equal seriousness and fun.

“I’m a Pisces, so that’s the fish sign,” Baker said. “I love water, I love fish and everything beachy. I probably would’ve been a beach flower child back in the day. I like hands-on field studies. We’re bringing relevant backyard science into the classroom.”

The objective of the classroom revolves around understanding how water is essential for all life and what we do in and out of the water, how it affects ecosystems and learning about being model citizens to nature.

“There’s a lot of real-life application from what we learn in this class to what you experience as you go on down the road,” Clayton said. “We make the water filters and practice getting the cleanest water we can use. Someone could’ve used that during Harvey or during the boil water notice.”

It’s also about understanding how algal blooms can affect what happens inside an aquarium and applying that to Galveston and why the beach should be free of people when there’s a tide.

“All of these things we touch on and teach in this class,” Clayton said.

Note: Kids easily shocked or can’t handle dissections are allowed to just observe or view a virtual demo of the dissection developed during COVID.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Bellaire High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Jane Baker • Mar 11, 2023 at 10:17 am

❤️ Nice job ? ?