‘I lost my escape’

English teacher’s experience with degenerative disc disease

English III teacher Brownfield (left) poses on top on Mount Katahdin in Maine in 2005. It was on her descent from this mountain when she began to experience shooting pains in her back.

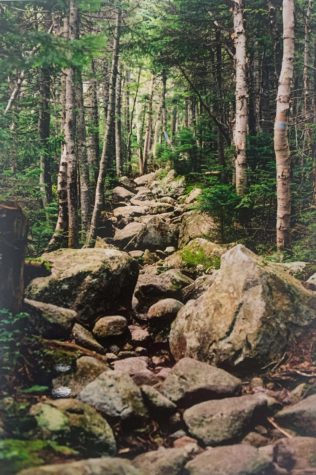

Descending Mount Katahdin, she knew something was wrong. Her 50-pound backpack continuously loaded pressure on her lower back. The tightness persistently heightened.

She would soon learn that her days backpacking would be cut short.

During her 2005 backpacking trip through the Appalachian Trail in Maine, English III teacher Mary Brownfield began to experience lower back pain.

“The pain began as pressure and tightness in my lower back,” Brownfield said. “A month after the trip, the pain became sharp. As the months went by, the pain became more pronounced, especially if I sat for long periods of time.”

For Brownfield, climbing Mount Katahdin, a part of the Appalachian Trail, proved a rigorous experience.

“The miles [hiked] changed day to day depending on the terrain,” Brownfield said. [My] approach to Mount Katahdin was a one-day, roughly 11 mile trip.”

When she returned to Houston, she saw a pain management specialist who diagnosed her with degenerative disc disease: a condition where the discs between the vertebrae of the spine lose their cushioning, causing pain and weakness.

Brownfield is not the only person in her family to suffer from degenerative joint disease. Her mother also suffered from such an illness, but Brownfield believes that backpacking compounded on the hereditary illness, causing the symptoms to arise earlier.

Despite the pain it caused, for Brownfield, her backpacking trip through the Appalachian Trail in Maine was an unforgettable experience.

“The heavily forested, rugged mountains and bogs were beautiful,” Brownfield said. “I saw lots of deer and moose.”

While she’s been on 10 backpacking trips, this would ultimately be her last. For Brownfield, losing backpacking was especially difficult because she’s felt a connection to nature since childhood.

“When I was a little girl, I loved getting away from the city and going off camping,” Brownfield said. “And my parents never enjoyed those types of things. My dad was your typical American who plays golf and tennis, and my mom didn’t do any of that.”

Being out in nature was far from glamorous though. On a longer backpacking trip in Georgia with her friends for 10 to 14 days, Brownfield battled swarms of ticks.

“We had to take regular tick-picking stops,” Brownfield said. “It felt like ticks were raining down on us, and we’d have to pull ticks out of the collars of our shirts and our hands. It was disgusting.”

In such secluded areas, showers were a rarity, so anytime she found a stream or river on the trail, Brownfield would make a stop.

“I would hop in with an organic all-purpose soap,” Brownfield said. “Wash [my] socks, clip them to the edge of my backpack, wash [my] body, wash [my] hair.”

For Brownfield, backpacking was an escape from reality.

“I felt strong and incredibly detached from the rat race of the city and incredibly attached to the wild,” Brownfield said. “It was realizing how small and insignificant my life was compared to nature, which is why I really loved it.”

Due to her diagnosis, Brownfield feels she lost an aspect of her life.

“I lost my escape,” Brownfield said. “I could never stand to do those long trips again because of the amount of weight and materials I had to carry in case of inclement weather.”

While her pain started out as shooting, about 2 years after Mount Katahdin it became more constant and debilitating.

“There were times where I couldn’t walk and get out of bed,” Brownfield said. “The sharp hot pain turned into a constant sciatica pain that went all the way down to my feet.”

This would lead Brownfield down a long path of tests, doctors visits and physical therapy.

“I ended up having a fusion [in my spine], so the doctor put in a riser to jack the two vertebrae away from each other and then added cadaver marrow,” Brownfield said. “That was a year-long recovery process.”

Despite her diagnosis, she still tries to incorporate shorter walks in her everyday life.

“I go hiking and I walk my dogs, but it’s not the same,” Brownfield said. “On a short day hike you’re going to be seeing people, but I only saw other people two times in Georgia. Switching from that, where you’re really in solitude, to the arboretum, I really feel like I’ve lost something.”

In addition to walking her dogs and solo hikes, Brownfield also travels with her friends. Last summer, Brownfield went to Peru with her friends Staci Davis and Mary Mulready to hike Machu Picchu. Despite Brownfield’s degenerative disc disease, Mulready believes that Brownfield did great on the hikes in Machu Picchu.

“She takes it easy and listens to her body,” Mulready said. “She knows she can’t push it or it can exacerbate pain in her back. When we would hike, she would only carry the essentials such as phone, water, sunscreen and hat.”

Davis believes that Brownfield is truly herself when she is out in nature.

“Hiking when she was young was her passion,” Davis said. “She is truly one when she is outside, whether it is working in her garden, playing with her dogs, or taking a day hike with friends.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Bellaire High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Dwayne Hansen • Mar 28, 2023 at 9:01 pm

That’s my teach!

Annie Greenhill • Mar 28, 2023 at 9:00 pm

I’m impressed with how you captured and shared Ms. Brownfield’s story!

Fiona Burrese • Mar 28, 2023 at 8:59 pm

Such a good story

Audrey Han • Mar 20, 2023 at 3:55 pm

Beautiful story!