One.

Two.

Three.

Three lashes for forgetting to do his homework.

It’s like nothing he’s ever experienced — worse than even breaking a bone, worse than when he’ll tear his ACL and MCL years later.

One. Two. Three. Three words he’s forced to say.

“Thank you, sir.”

But those are the only sounds he can make.

There’s no crying allowed, and if he screams, he’ll be sent in for another caning. Instead, he bites his tongue. Straightens his back. Tugs up his pants.

He walks out the door.

The next boy walks in.

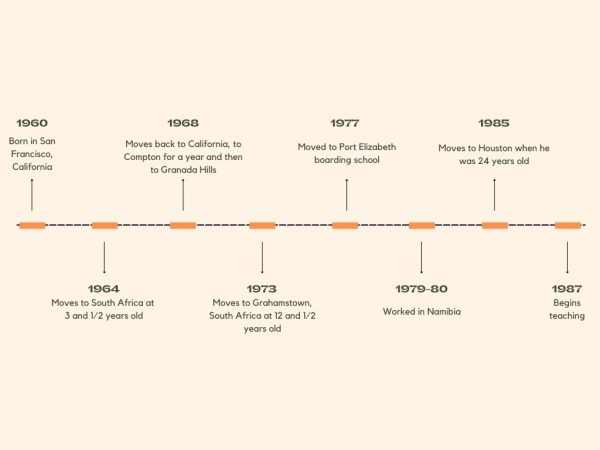

Theory of Knowledge and world geography teacher Gregory Switzer discovered the harsh reality of South African life at 3 years old, freshly transplanted from San Francisco.

Both of his parents were professors, completing migrations every four years from the United States to South Africa. His childhood was caught between California and Cape Province, America and apartheid, civil rights and civil strife.

“I’d say my childhood was somewhat tumultuous because I moved around a lot,” Switzer said.

His family moved to Grahamstown, South Africa, a small college town, at age 12. He would stay in South Africa until he turned 24.

“I was always remaking friends, trying to adjust to the circumstances,” Switzer said. “South Africa back in those days was under apartheid. It was very different from California.”

Visiting townships in high school, Switzer said they had no plumbing, a running faucet every two or three blocks, and shelters built out of whatever they could find because wages were so “incredibly low”.

“[It] was pretty awful,” Switzer said. “[I saw] lots of young children that were malnourished [with] distended bellies.”

He said his peers, however, remained ignorant.

They saw the rounded bellies of those children and thought that they were “well-fed and chubby.” But the swelling was actually caused by kwashiorkor, fluid retention brought on by severe malnutrition and little medical care.

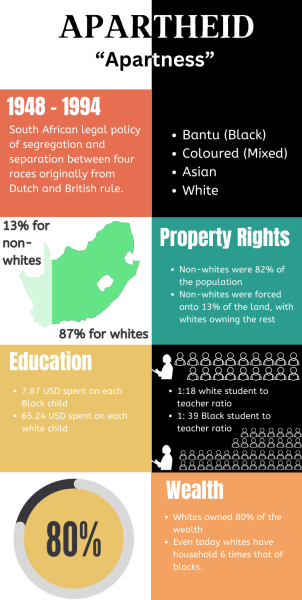

As Switzer grew older, the absurdities of apartheid became more evident to him.

“If you were Chinese, you were considered ‘colored,’” Switzer said. “If you were Japanese, you were white. It was beyond stupid.”

Switzer also faced caning for “menial” misdemeanors in high school. Talking in class, untucked shirts, unfinished homework, failing a test and unpolished shoes were all grounds for corporal punishment.

He remembers being caned 30-40 times throughout his high school career.

“What happened to me would be a major crime here,” Switzer said.

There would usually be other boys waiting with him. Some of the screams were loud enough to be heard down the line.

“You don’t want to be in the back of the line,” Switzer said. “[But] sometimes if it was a really long line, you don’t get hit as hard as the people in the front of the line. It was a double-edged sword.”

College was different.

No more canings.

In fact, Switzer explained that the prevalence of corporal punishment in high school was one of the reasons why so many young South Africans failed in college. Students were given freedom after such brutal restrictions, and they didn’t adapt well.

College might have been different. But many of his peers remained the same: largely apathetic towards apartheid.

“They knew things had to change,” Switzer said. “But most of them benefited off of [it].”

Switzer and a few of his classmates attended apartheid protests, which were frequently shut down by military gunpoint. But other peers still believed that colonized countries were “lucky to have the colonizing country there to teach them civilization.”

As soon as Switzer finished college, though, new South African naturalization laws forced him to enlist in the military.

“I left [South Africa] the day I was supposed to go to basic training,” Switzer said. “I would have had to go fight to preserve apartheid, which was something I couldn’t morally condone.”

Switzer moved to Houston and took the first job he could find: spray blasting and spray painting.

Once he got state residency, he worked nights at UPS and went to school during the day to get his teaching certification.

“I thought that with all my life lessons, I could do it better than the way I was taught,” Switzer said. “I’ve seen most of the good and bad this world has to offer.”

He started at McReynolds Middle School, next taught at Lamar High School for three years and then taught World Cultures at Pin Oak Middle School in 2007, where he met Ann Linsley, Bellaire IB coordinator, beginning a 20-year-long friendship.

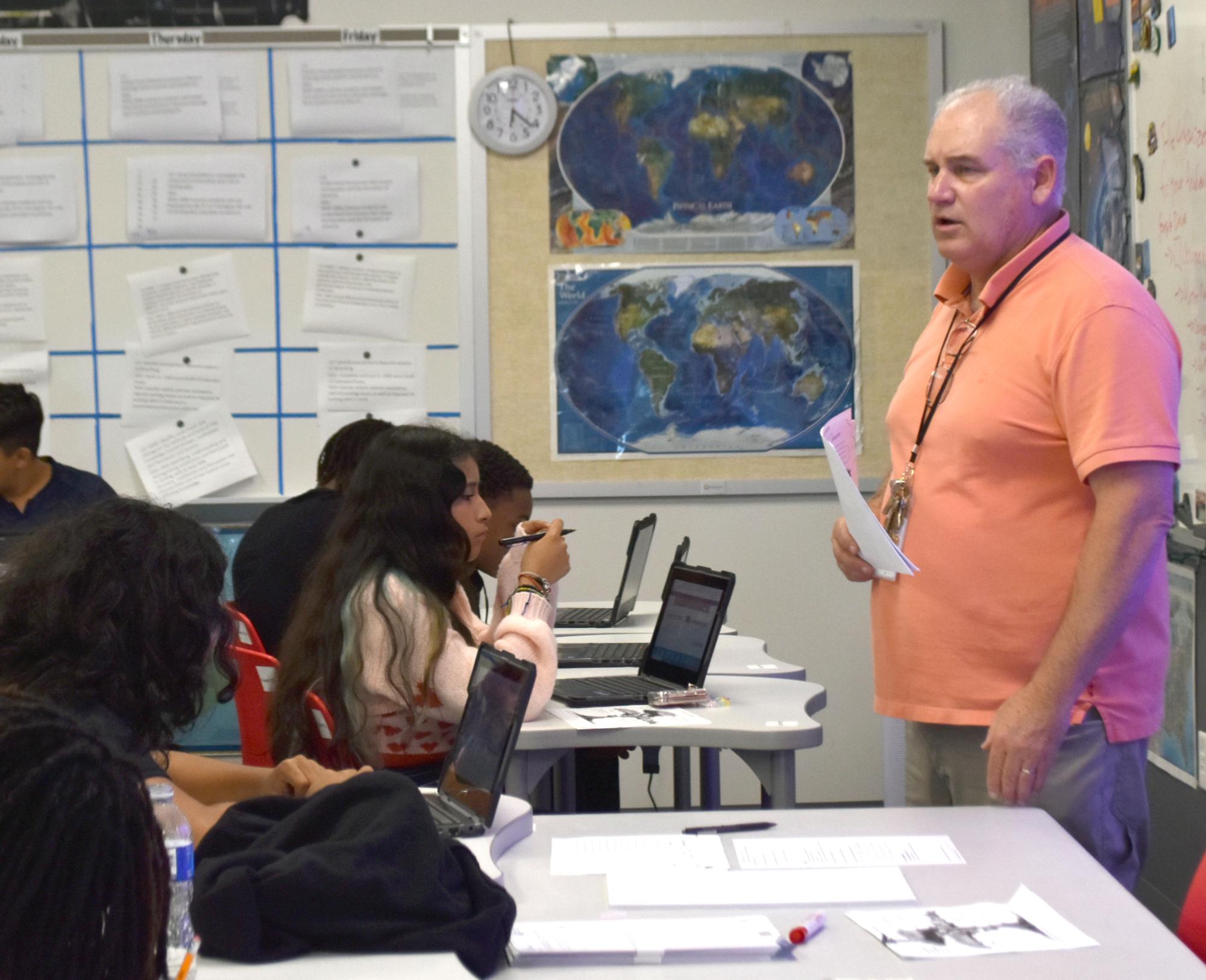

“He makes you think,” Linsley said. “He makes the students think, challenges them on what they think and why they think what they do.”

When Switzer was ready for a change in 2022, Linsley recruited him to fill the recently vacated Theory of Knowledge position, which he would teach in conjunction with ninth grade geography. Theory of Knowledge, an IB required class, emphasizes developing critical thinking to evaluate both what students know and how they know it.

To be able to have somebody with those kinds of skill backgrounds was incredibly important, according to Linsley.

”He has the criteria and the credentials to be able to teach the Theory of Knowledge class the way it needs to be done to bring out that depth of thinking and analytical development,” Linsley said.

At Bellaire, Switzer reconnected with many of his former students, including senior Carlo Masciangelo who took his world cultures class in 6th grade.

“Mr. Switzer always kept it real with me,” Masciangelo said. “He’s probably my favorite teacher I’ve ever had. Every time I walked into his class, it felt brighter than all the other classrooms.”

Masciangelo said that Switzer was one of the only teachers he enjoyed.

“I was very engaged,” Masciangelo said. “When I walked in there, it’s like something in my brain just clicked, and I was like, ‘I can’t wait to listen to this guy in class.’”

Switzer believes that teaching is not about the income: it’s about encouraging students like Masciangelo.

“You don’t really go into teaching for monetary gain or even a good pat on the back because you’re not going to get either,” Switzer said.

“You do it for the kids.”

Clementine Behelfer • Nov 4, 2023 at 9:45 am

Such an interesting story!

Emma Xiao • Oct 5, 2023 at 8:16 am

A phenomenal story!