Sarah Shado’s goal is simple in writing.

Pick up the scalpel, make an incision and complete the task at hand.

As a forensic enthusiast and first-year on-level biology teacher, Shado emphasized that. Forensics is more than a cut here or a chart there. It is a window into the world of the dead that gives families the answers they desire regarding how the victim died.

Shado’s passion for forensics and criminal justice goes all the way back to her father watching crime cases on ID Investigation coupled with her love for science from a young age.

“I’ve always been fascinated by the intersection of science and justice,” Shado said. “I gained valuable insight into all aspects of forensic pathology.”

Shado has a master’s degree in forensic science and is working to obtain her doctorate in criminal justice with a focus on leadership. According to Shado, forensics is not an easy field to work in, emotionally or practically.

“It’s about compassion for the lives affected,” Shado said. “For example, the JonBenét Ramsey case showed me how important proper evidence collection and analysis is since missteps in forensic work can impact justice for years to come.”

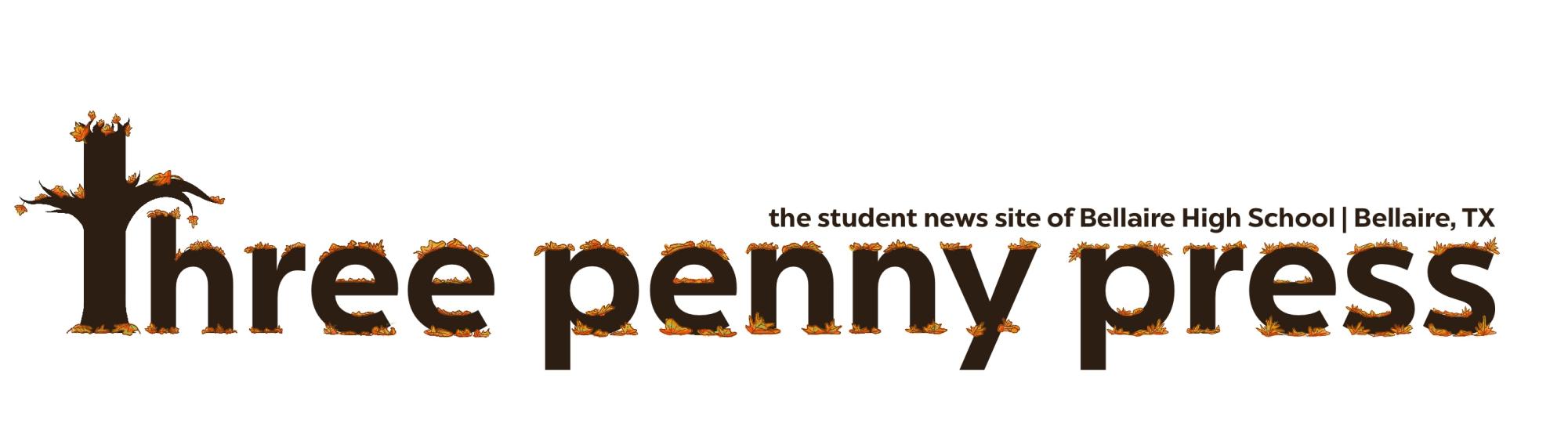

Shado began working as an intern at the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences (ADFS) on Aug. 21, 2023. After a month, she was promoted to wet tech, in charge of making incisions and removing organs. Shado was the fastest person in her workplace to be promoted from intern to wet tech.

During her time working with ADFS, Shado learned to distance herself from her emotions. However, on her first day, she learned that “suppressing them can only go so far.”

Autopsies are crucial to forensic investigations—however, they are difficult and taxing and therefore require people with Shado’s level of experience to perform them.

“At most, I did three autopsies a day,” Shado said. “I did about 12 [to] 15 a week.”

With the increase in overdoses, Shado’s work became more and more demanding. As her work progressed, the realization occurred that she was working with victims — not just a case, a number or a chart, but a victim at the hands of an accident, others or even themselves.

“We got everything,” Shado said. “Most were homicide and drug overdose — especially fentanyl.”

When dealing with cases similar to the type Shado encountered on the daily, forensic death investigators are forced to take a new and objective perspective. According to Shado, her first day was “difficult and eye opening” at the same time.

“My first day as a wet tech intern was both overwhelming and exciting, and the two cases I worked on were brutal, which hit me hard mentally and emotionally,” Shado said.

She said that all she could do after her first day was “[taking] a shower, [sitting] in the dark and [going] to bed.”

Shado quickly learned that the emotional strain from working in the forensic field is taxing on mental health. Shado stated that seeing dead bodies on TV is incomparable to working with them first hand, and that the sympathy felt can be overwhelming.

She takes the liberty to teach students about forensics, with topics ranging from emotional stress to in-depth case studies. Shado is the sponsor of Bellaire High School’s Forensic Science Club, where she uses her past knowledge to teach intricate lessons and to further her career by gaining valuable experience. The Forensic Science Club attracts both upper and underclassmen with its engaging lessons.

“Ms. Shado’s work with autopsies made her more experienced in knowing what to look for in the case studies for our club,” junior and Forensic Science Club member Eden Wilson said.

Shado’s knowledge and love for science can be found not only in her devoted club members but also in her students, who find her class to be a highlight of their day. Her teaching style has influenced many freshmen to deepen their engagement with Bellaire extracurriculars such as the Forensic Science Club.

“I would love to go to the Forensic Club because I feel like it would give me an opportunity to learn more and see what she teaches outside of just biology,” freshman Alexis Gibson said.

Shado teaches with the hopes of enriching her students in biology — a field which plays a crucial part in forensic science. Teaching is a significant part of Shado’s journey to become a leader in the forensic science field.

“My ultimate goal is to become a CEO or director of a major forensics or criminal justice organization, leading teams that make a real impact in the field,” Shado said.

Despite her original intentions to become a forensic pathologist, Shado is taking her time to ensure that she is the best that she can be going into a field which requires knowledge in autopsies, biology and leadership.

“In the meantime, I am focused on acquiring all the necessary skills and ensuring that I become the best of the best in both forensics and criminal justice, since the two fields are so closely connected,” Shado said.

While pursuing her career, Shado expressed the influence of several mentors—notably Dr. Javan, Shado’s thesis advisor and forensic biology teacher while she pursued her master’s degree at Alabama State University.

“Her work as a death investigator and all the amazing things she accomplished in the forensics field inspired me deeply and shaped how I strive to approach my own career,” Shado said.

Training under such mentors gave Shado a keen eye for detail and care for proper evidence collection and analysis, as well as reinforcement of her values of accuracy over dramatization.

Shado’s goal lies where the past meets the present. Her prior experience as an autopsy tech created a world of opportunity to learn from her mentors and pave a new path in the world of forensic science.

“I not only follow in the footsteps of those I respect, but I also contribute to positive changes in how the field operates,” Shado said.