The wisest hands I have ever touched

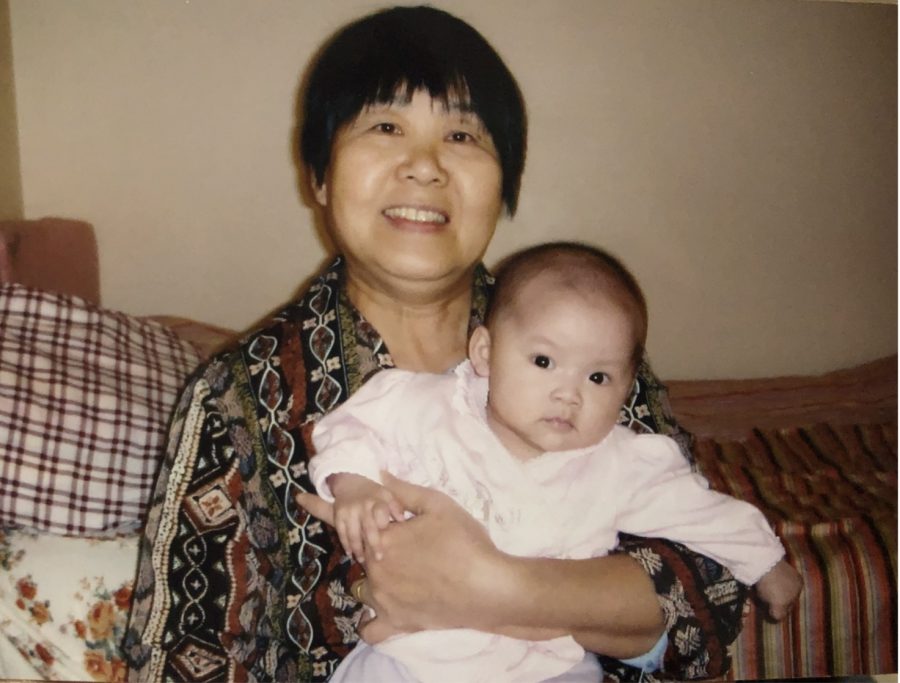

My laolao holding me in her arms in 2006. She visited us in Columbus, Ohio.

When I think of my laolao, my grandmother, I think of her hands.

They were not pretty. But they were the hands of a worker, sun-tanned and weather-beaten, with thick fingers and rough, calloused palms.

Those hands were the wisest hands I have ever touched.

When I was in preschool, my laolao came from China to visit us. She walked to my school to pick me up, often bringing a bag of dried salted plums. She held my hand with her left hand, and when I needed to spit out the pits of the plums, she offered her right hand to carry the sticky pits back home. As cars whizzed past us, she was the only anchor available to me. She always held me in her tight hands.

My dad often reminisces about my laolao’s cooking. I saw her making dumplings when I last visited her in 2017. Her hands, dusted with flour, danced across the wooden board, rolling and kneading and pinching the dough. It was mesmerizing. The finished dumplings had blooming bellies and a rich, juicy filling. When compliments were thrown her way, she would just nod and say, “Good.”

I miss the gentleness of her rough hands, the same hands that massaged former President George H. W. Bush during his visit to Beijing in 1989. My laolao was a masseur at a hotel. “I was recommended to him,” she told me, a proud glint in her eyes. She told me this after giving me my own massage, lulling me to sleep with her strong hands.

My laolao had brave hands. She caught rats in her house with her bare hands and tied them in plastic bags to suffocate them. Once, she used her fearless hands to snag a giant cockroach off the wall in our old apartment. My mother was appalled. “I’m old,” my laolao said. “Getting my hands dirty is the least of my worries.”

Even after she was diagnosed with colon cancer, my laolao continued her stroll to the markets. I went with her sometimes to help drag the blue cart she took with her. Her hands examined each fruit and vegetable with precision, her fingers feeling for any bruises or holes. She was always careful.

There were times when my laolao’s hands could not do their job. On my last trip to Beijing, chemotherapy had dried her skin to an extreme. My mom used her hands to scrub my laolao’s legs and arms, the skin flaking off in torrents. “It’s like a snowstorm,” my mom joked, but it was strained.

At the end of my trip in 2017, I said goodbye to my laolao, and we hugged and cried together. It was my first time seeing her cry. She looked incredibly frail and small. A few surviving pieces of hair stuck out of her beanie, and her clothes hung limply on her thin frame. But her hands, pressed against my back, felt as strong as ever.

She passed away two years later. I received the news over the phone from my mom, who had been taking care of her in Beijing. I don’t remember if I cried or not; I just felt numb. Grief is like that.

My laolao’s hands had stories etched into the wrinkles, which she told through every dumpling she made, every forehead she smoothed and every hand she held. Even if I was to shake the hands of every person on the planet, I wouldn’t have touched any hands wiser than those of my laolao.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Bellaire High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Irene Zheng • Apr 16, 2023 at 10:20 pm

Incredible writing! Love the way you shared this story.

Rilina Tran • Apr 15, 2023 at 9:49 am

Also, you were such a cute baby!!

Rilina Tran • Apr 15, 2023 at 9:48 am

Wow, Emma! This was truly breathtaking. I love reading all of your stories, but this one truly hit home!

Angel • Apr 14, 2023 at 2:16 pm

Great story Emma! It made me tear a bit…

Helen Beebe • Apr 14, 2023 at 9:20 am

this is ever so beautifully written.

Blen • Apr 13, 2023 at 2:09 pm

this is such a heartwarming story Emma!

Marina Martinez • Apr 13, 2023 at 1:44 pm

This is such a beautiful story, amazingly written :))

Aniket Panicker • Apr 13, 2023 at 8:34 am

An incredibly moving story written by an incredibly talented writer. Well done Emma!

joy • Apr 12, 2023 at 9:17 pm

Your writing style sounds so pretty!

Nabila • Apr 12, 2023 at 11:52 am

beautifully written emma!!

Audrey Han • Apr 11, 2023 at 10:46 pm

As always, beautiful writing Emma <3