This review contains spoilers for the animation “The Boy and the Heron.”

Japanese filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki has finally returned with what might be his final creation: “The Boy and the Heron.”

Following Miyazaki’s retirement once again in 2013, I have been highly anticipating his new film after a decade of inactivity.

Released on Dec. 8, Studio Ghibli’s latest movie is said to be a massive letdown by some fans who have watched other similar productions such as “Howl’s Moving Castle,” “Spirited Away” or “My Neighbor Totoro.” Considering these are very successful and well-known masterpieces, it’s not a surprise that a more mysterious, mature film would be rated lower.

However, “The Boy and the Heron” still displays elements similar to those that the young audience of Studio Ghibli desires: adventure, magic and fantasy.

Titled in Japanese “How Do You Live?,” the animation is adapted from a 1937 novel by Genzaburo Yoshino. Both highlight grieving, moving on and accepting the death of others.

The scene is set three years into World War II. A young boy named Mahito Maki catches sight of his mother’s hospital exploding into flames. This is one of the first times I’ve seen Miyazaki create such harsh settings, considering he rarely embodied violence in his previous movies. And although his rough strokes of gray, darkness and chaos surprised me, I enjoyed the sudden clash from his usual style.

Mahito flees to the countryside with his father. I love how the scene completely transforms into vibrant cool hues of nature. Miyazaki parallels the storyline with his personal life as he almost lost his mother to tuberculosis and fled Tokyo in the 1940s with his father, a warplane mechanic, similar to Mahito’s father. I find Miyazaki’s semi-autobiographical plotline to be a meaningful element that he intended to incorporate into his final masterpiece.

After the loss of his mother, Hisako, Mahito is weary about accepting his new mother because his father immediately remarries his wife’s sister, Natsuko, who is now pregnant, which I found absolutely shocking. So, in the rural landscape, he has trouble adjusting to his new home, his stepmother and old maids. With the melancholy music and endless fields blowing in the wind, I could only feel sorrow for the sudden rush of unrealistic changes that Mahito experienced.

Something strange that caught my eye were the long moments of silences throughout the scenes. I noticed there was only some dialogue between characters and the majority of the movie consisted of montages, piecing together short clips of scenes that introduced new settings–similar to fast-forwarding clips of time. There was no sound other than the soft orchestral music, gentle breezes or cascading tides in the background.

Mahito soon becomes acquainted with one of the old maids, Kiriko, who I picture as a sweet grandmother looking after her grandson. As Mahito is bullied at his new school, he begins to self-harm. Again, this only came as a huge shock to me from Miyazaki because he demonstrates very mature aspects of life as Mahito blossoms away from childhood.

I think this is where the Gray Heron swoops in as a guide and friend who introduces Mahito to a new realm: the land of the dead. Now, it might not look like it with its vast open green fields and vivid empty blue ocean, but I interpret this as where the dead reside, including Mahito’s mother.

The heron, or sagi in Japanese, symbolizes spirits, death and connection to other worlds. Therefore, it’s no coincidence that a strange man dressed in a heron’s skin would guide Mahito to move on from grievance after searching for his mother.

One element I absolutely love is how Studio Ghibli never fails to insert little creatures into every film–they’re always my favorite characters. For instance, there are the soot sprites in “Spirited Away,” human-like goldfish in “Ponyo” and kodama tree spirits in “Princess Mononoke.” In this case, we have warawara: small, white and bubbly characters that float in the sky. On the other hand, we also have giant human-sized parakeets who have a hungry appetite for humans as well as pelicans who feed on the warawara.

The redundancy of birds throughout the film makes me envision them as messengers of death. My deeper interpretation of the gray heron illustrates him as Mahito’s escort away from death and possible suicide. Additionally, I imagine the pelicans and parakeets symbolize the need for their own survival in a humanistic society, represented by the last words of a dying pelican that Mahito finds as well as the feature of the vengeful Parakeet King.

Towards the end of the movie, the swaying of the stack of wooden building blocks had me on the edge of my seat. I never would have imagined that Mahito’s great-grand-uncle was the creator of this magical realm.

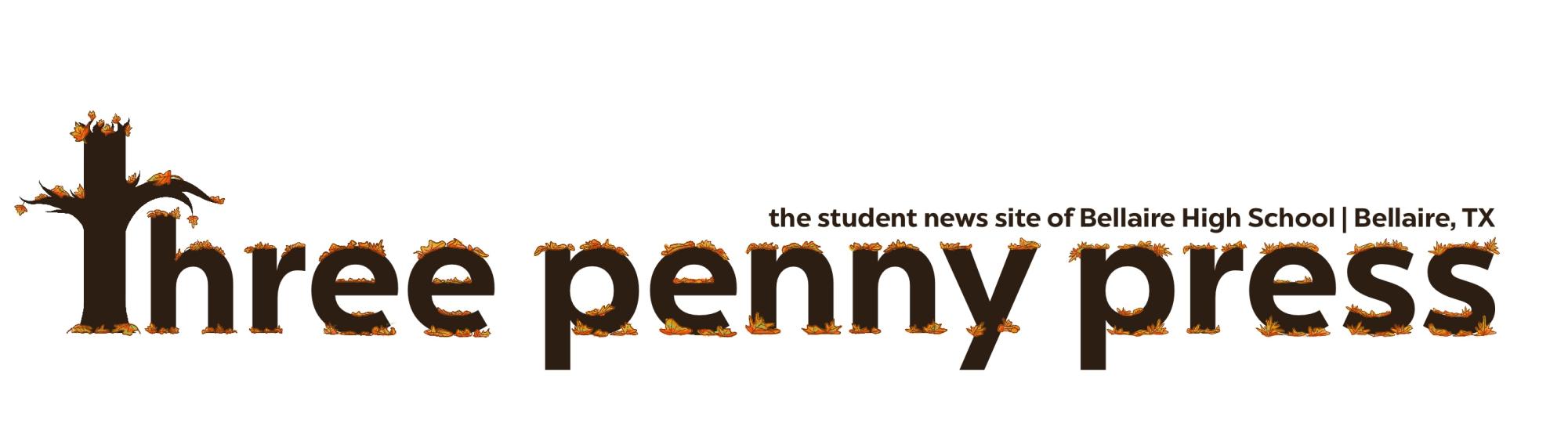

But as the blocks toppled over and the world slipped away from under, I was partially glad that the Parakeet King put an end to the parallel world. Despite Grand Uncle’s efforts to make Mahito stay, I thought it was about time for him to let go of a domain created by his mind. My favorite part was when Mahito jumped through the portal door after hugging his mom for a final time, light pouring into the scene. The parakeets, now normal-sized, flew into the bright blue sky. It was a perfect loop into the real world.

Following his return, I felt at peace that Mahito had grasped the idea of death and grief, letting go of his mother but keeping her in his heart. After a couple of years, he and his new family move back to Tokyo.

I feel almost heartbroken that Miyazaki is saying goodbye and establishing his last mark before leaving us. He wraps up this film beautifully by circling it back around, but with a different perception of life. The contrasting parallels not only help us witness the path to healing, but also to embrace the dawn of a new beginning.