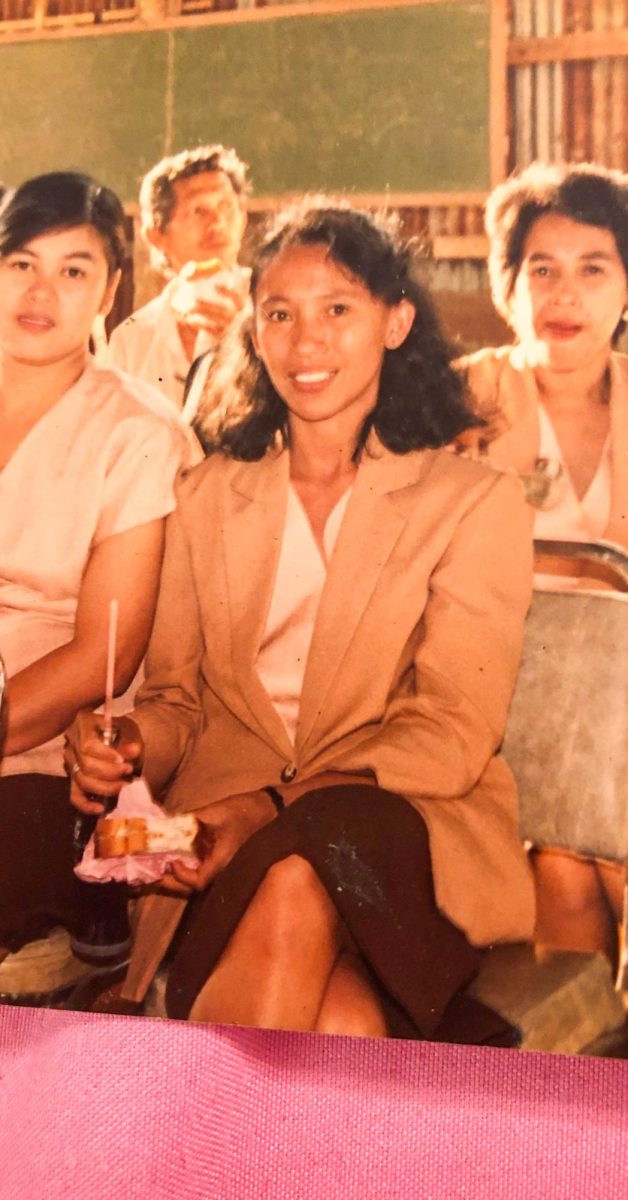

She walked barefoot for two hours every day, rain or shine.

Wearing her one and only uniform, she made it to school, exhausted but never deterred.

Living in Don Carlos, Bukidnon, in the Philippines, 7-year-old Conchita Bean didn’t have the luxury of school as a right. For her, it was a privilege.

“We didn’t have school buses,” Bean said. “I would walk for two hours just to go to school every day with no shoes on.”

Algebra 2 teacher Bean grew up with a love of learning, but poverty stood in the way of her dream.

“Because we were very poor, I had to harvest rice and corn so I could buy a pen, paper and a spiral notebook,” Bean said.

She grew up in a family of farmers on an acre of land planting rice, cassava, coconuts, bananas and other crops.” They found difficulty in making ends meet, forcing her to become resourceful when finding school supplies.

“I had to put my stuff in a transparent plastic bag,” Bean said. “And if it rained, I didn’t have an umbrella, so I’d get a big banana leaf to cover my head.”

Money also became a barrier to completing school projects as the necessary supplies were unaffordable.

“I would ask the teacher, ‘Can I do something else? Something I can make at home?’” Bean said. “For example, if I had an embroidery project, I would have to buy a piece of cloth, make a design and embroider. I didn’t have the money to buy a piece of cloth. I didn’t have the money to buy embroidery. I didn’t even have the money to buy thread. I was the poorest of the poor.”

But instead of giving up, she found a creative solution.

“I gathered feathers from roosters and completed the project in my own way,” Bean said. “I brought the feathers in a plastic bag and then made a beautiful feather duster with many different colors myself.”

That mindset left a lasting effect.

“My teacher was very impressed,” Bean said. “She told me, ‘Conchita, you will succeed in the future because you are very resourceful.’”

Bean’s determination extended beyond just school.

“If I had extra money from harvesting, then I would buy some clothes, not very new clothes, but at least I’d have something,” Bean said. “I would see my friends with smooth, clean clothes and beautiful school bags, but I just kept telling myself, ‘Someday I’ll be able to wear what my friends have. Someday I’ll have beautiful shoes, and my clothes are going to be beautiful dresses.’”

Even at home, her commitments never ceased. Her family’s farm often came first.

“My brother would want me to take a day off from school [to] take care of our farm,” Bean said. “I would cry and [say], ‘I will help the farm Saturdays and Sundays, but just let me go to school.’”

Her motivation to work for her opportunities stemmed from a single moment during her childhood, one that would stay with her forever.

“On the very first day I went to school, I saw farmers in the field,” Bean said. “I was seven, and I told myself, ‘I don’t want to be working in the field forever. I think there’s something in school that is better.’”

Bean finished elementary school at Bocboc Central Elementary School at the top of her class, but high school brought a new challenge.

“At the time, high school wasn’t free,” Bean said. “I took one year off from school and worked as a babysitter for my previous teacher so I could save money.”

But even after a year of work, her savings weren’t enough to cover tuition. Ever motivated, Bean turned to her mother, adamant about continuing her education.

“I told my mother, ‘I really want to go to school,’” Bean said. “While my classmates were already in high school, I was still trying to find a way to go.”

Her family didn’t have enough money to enroll her at San Isidro High School outright, so they arranged to pay tuition over time. It took a year of planning and harvesting crops to cover each payment. Whenever a test was coming up and she couldn’t afford the fee, Bean went to the principal’s office to ask if she could take it and pay later.

“By the end of the year, I was able to pay it all off, and I became the first honors in my class,” Bean said. “I was granted a scholarship from the second year to fourth year of high school.”

Financial limitations further limited Bean’s chances of becoming a chemical engineer, a dream she had had for years.

“Since we were so poor, I wasn’t able to get a scholarship for engineering,” Bean said. “[But] when I was going through college, there was a shortage of teachers in the Philippines, and my university offered scholarships if you took the National College Entrance Examination and scored 95 or above.”

Her score? 97.

“That was the only option available to me,” Bean said. “So I took it.”

The scholarship was for education, not engineering, but she seized the chance anyway. She graduated from Bukidnon State University with a Bachelor of Science in Secondary Education, majoring in math.

Although she hadn’t initially planned to become a teacher, with just one year of teaching after her bachelor’s degree, Bean realized she truly loved it. She discovered the impact she could have on students and knew that fate had led her to the right place.

“I love teaching,” Bean said. “So I told myself, ‘I must really be a better educator.’ I finished my Master’s Degree, majoring in mathematics while being a full-time teacher at San Isidro College, full-time housewife and full-time mother.”

For 18 years after, Bean taught in the Philippines, spending one year at the San Agustin Institute of Technology and six years at San Isidro College, both private schools, and 11 years at Bukidnon National High School, a public school. But when she moved to the United States on July 15, 2000, she was met with a completely different environment.

“My transition from the private school to public school back home was not that different, because students back home are very motivated to learn,” Bean said. “When I came here, it was the opposite.”

Bean first started her American teaching career at Lee High School, where she had to learn how to overcome the cultural differences she faced.

“You just turn your back, and [students] will unplug the overhead,” Bean said. “I called my principal back home [and] told him, ‘Take care of students there, because the most problematic student back home is an angel compared to students here.’”

That was 25 years ago. Since then, Bean has altered her teaching style accordingly, becoming a bit more strict while also learning the importance of building connections with students, something she had to learn “the hard way.”

“Back home, a teacher needs to be sweet and nice,” Bean said. “I thought, when I came here, that is how I was supposed to be. It is very different here. Students take [being] sweet and nice as a sign of weakness.”

Even through the challenges, Bean never lost her passion for math or her desire to connect with her students.

“I think she was a great teacher,” Wesley George, one of her former Pre-AP Algebra 2 students, said. “I think I performed really well in her class, and that’s in part because of her. She had a really good balance of teaching and letting us learn on our own.”

For George, it wasn’t just about the math lessons but about the way Bean treated him during a difficult time.

“I was having schedule complications because my grandfather’s funeral fell on a date of the math exam, and I had to be out of state,” George said. “She helped me organize the makeup test, and she let me come back. That felt so special because she understood how stressed I was and didn’t give me any consequences.”

His friendship with Bean extended beyond the class.

“One of the many blessings of having her as a teacher was that she was also my club sponsor for the Southeast Asian Student Association,” George said. “She would let me use her room for events and movies, and I really appreciated having her be part of that cultural expression.”

George isn’t the only one who’s felt Bean’s commitment. Her colleague, Jean Carcedo, remembers her first connection with Bean before she even stepped into the classroom.

“I met Ms. Bean when she sent me an email asking if I was Filipino,” Carcedo said. “At the time, I was the only Filipino in the math department, so she wanted to reach out and see the school from my eyes.”

From that first interaction, Carcedo saw Bean’s openness to connect. That same energy carried into their work together.

“Ms. Bean is always ready to extend a helping hand as she has a hard time saying no,” Carcedo said. “She is someone that you enjoy working with because she has a strong work ethic, and as our friendship grew over the years, I consider her a genuine friend.”

Every lesson Bean teaches carries not just numbers on a board but the story of a woman who walked barefoot for hours to get to school and has never stopped walking toward her purpose since.

“I think the hardships made me stronger,” Bean said. “They made me love this job even more. Because after all, a teacher is there to help you. We’re not here to punish students. We are here to help students.”

David Morgan • Sep 26, 2025 at 9:30 pm

Ms Bean’s story is so motivating, this is what I call a resilient person! She didn’t give up, she took the challenges life gave her and came out triumphant like a true champion!

It was nice having her as my PreAP Algebra 2 teacher last year (2024-2025) 😊 and even though I’m absolutely terrible at math and thought of quitting, I decided to stay because I felt comfortable in her class, I knew I could ask questions when I didn’t understand a thing and we developed a good teacher and student friendship. 😃

Conchita Bean • Sep 30, 2025 at 11:14 am

Thank you David. It was a pleasure having you in my class.

Rajan Vyas • Sep 24, 2025 at 2:39 pm

Very nice story

Camila Chandler • Sep 23, 2025 at 10:23 am

Such a moving story. What a great addition to the feature section 🙂

Alia Hassan • Sep 19, 2025 at 9:12 am

You guys did an amazing job!! Truly a special feature!

Audrey • Sep 19, 2025 at 8:33 am

This is such a moving story!

Mallika Mohan • Sep 19, 2025 at 7:40 am

This is so sweet and heartwarming, great job Cindy and Ayana!

Angelina Tao • Sep 18, 2025 at 11:17 pm

wow, such a great story on resilience and passion! excellent job!

Joy Xia • Sep 18, 2025 at 10:41 pm

Incredible story about an incredible teacher! Thank you Ayana and Cindy, and thank you Ms. Bean for your dedication.