We still need affirmative action

Feb 1, 2023

Affirmative action, a policy that has been in place for 61 years, is now threatened in light of the 2014 Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College lawsuit which reached the Supreme Court in 2022.

But what exactly is affirmative action?

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines affirmative action as “the use of policies, legislation, programs, and procedures to improve the educational or employment opportunities of members of certain demographic groups … as a remedy to the effects of long-standing discrimination against such groups.”

After being coined in the Wagner Act of 1935, the term was linked with conversations surrounding the advancement of racial equality when President John F. Kennedy signed Executive Order 10925 in 1961.

Former President Lyndon B. Johnson continued the executive push for equal opportunity by ordering employers and college admission officers to consider race when looking at an application.

College admissions officers implemented racial quotas to comply with former President Johnson’s order, using race as a determinant for admissions. However, quotas were deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1978. Justice Lewis F. Powell declared that racial classifications require the application of “strict scrutiny.”

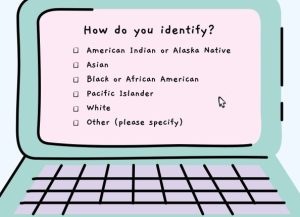

Today, instead of viewing race as a determinative factor in order to meet a quota, college admissions officers often classify race as a “plus factor,” meaning that it is one factor out of many, which contributes to one’s acceptance into a particular university.

However, those who oppose affirmative action still argue that it is inherently discriminatory by giving racial minorities an advantage in college admissions.

But this isn’t the case. Affirmative action is a policy put in place to undo the racist policies that have left marginalized communities at a disadvantage when receiving an education.

The increase of equity in our nation that comes with affirmative action acknowledges the different needs of applicants in a way which enables them to all have the same opportunity to succeed, combating underrepresentation of minorities at universities.

Racial demographics are also negatively impacted when affirmative action is removed. For example, the University of California Berkeley’s number of Black students dropped from six percent to three percent between 1980 and 2022 after California’s ban on affirmative action in 1996.

Racial diversity also does much more than just help students of color.

A common alternative provided for affirmative action policies is to simply give a plus factor to those with a lower socioeconomic status. It is argued that it would still give those with a lack of resources an equal opportunity to succeed in their education. While this is true, this argument assumes that affirmative action only serves to help those at an economic disadvantage instead of everyone.

In reality, socioeconomic and racial diversity paired together help in all areas of society, especially in the classroom. They increase overall academic achievement, break down barriers by decreasing prejudices and stereotypes, and increase success in the global marketplace.

Even more so, in 2015 Fortune-100 and leading American businesses –including Apple, Microsoft, United Airlines and Walmart– asserted to the Supreme Court that graduates of all races from racially diverse universities have “an increased ability to facilitate unique and creative approaches to problem-solving,” are “better equipped to understand a wider variety of consumer needs” and are “likely to generate a more positive work environment by decreasing incidents of discrimination and stereotyping”.

However, after reaching the Supreme Court in 2022, the Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard case has threatened affirmative action on the basis that the policy hurts the chances of Asian American students gaining a spot at America’s selective universities. SFFA’s argument that affirmative action is discriminatory is based on the fact that Asian Americans consistently score higher than white, Black and Hispanic applicants on SATs and have higher academic achievement overall but do not make up a majority of the student population at Harvard.

This argument that higher test scores are equivalent to higher acceptance rates implies that test scores are the only factors that should go into getting accepted into a university. According to the College Board, factors including personal statements and essays, recommendations, extracurricular activities and interviews are also taken into consideration by college admissions officers.

Founder and president of SFFA Edward Blum, who is a Bellaire alumnus, also points to disparity between the number of Asian American applicants and the number of Asian American students at Harvard to make his case.

“The nation cannot remedy past racial discrimination with new racial discrimination,” Blum said. “For over 20 years, Harvard’s admission rate for Asian Americans hovered year after year around 18 percent, even though the number of Asian applicants to Harvard increased dramatically.”

While the amount of Asian Americans accepted into Harvard might have stayed steady despite an increase in applicants, they are still overrepresented compared to other minorities

In addition to this, a general population increase coupled with more students attempting to receive a higher education in recent years would account for the rise in the number of Asian American students applicants.

“[Asian Americans’ acceptance rate into Harvard] indicates that Harvard had a quota in place to limit the number of Asian Americans it would accept,” Blum said. “Today, only after Harvard was sued, the Asian American admission rate has increased to nearly 28 percent.”

The accusation of Harvard’s use of a quota is a clear indication that this court case should not be about affirmative action. The use of quotas has been unconstitutional since 1978 and is no longer a process associated with affirmative action.

SFFA should only be suing on the grounds that Harvard is violating the Civil Rights Act of 1964. However, Supreme Court Justices may still be inclined to outlaw affirmative action policies altogether in order to avoid future conflicts such as this one.

The threat the Supreme Court places on these policies hurts the chances of millions of applicants and decreases the overall diversity of those receiving a higher education. In states in which affirmative action is outlawed —Alabama, California, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas and Washington— the number of students of color admitted to colleges decreased by 23 percent after affirmative action was banned. Removing these policies only serves to harm those who need support the most.

Affirmative action isn’t perfect. In order for us to truly achieve equality and diversity in our educational environments, K-12 schools would need to receive much more aid and resources to set children up for achievement in the later stages of life. Maybe someday we’ll reach a point where policies such as affirmative action aren’t needed anymore. But as of now, to ban affirmative action would be a step in the wrong direction and would ultimately hinder the academic pursuits of high school students across the country.

Johanna Wen • Feb 15, 2023 at 12:55 pm

“Treating everyone equally does not mean equality” is a good way to describe this difficult topic to solve, but it’s also the other way around. I am a biracial student (Cantonese and White American) I have the option to “choose one,” but I don’t want to consider myself lucky for that reason. Discrimination is not equal, but it’s also not justified when leveling out the “playing field.” My father, similarly to Theo Hunt, said that “you have to know the rules, especially when they’re unfair.” And while we can wish and act upon “immediate resolution,” like dropping worrying about race, there are still so many nuances that we need to consider.

Theo Hunt • Feb 5, 2023 at 11:27 am

As an Asian American, I have a few issues with this article. While I understand that yall tried to show both sides of the debate, especially for Asians, the evidence used for Harvard is extremely cherrypicked. If just looking at Bellaire, I know many mixed race Asian students that prefer to be identified as Asian but have already or plan to exclude that on their college apps. All of this is because of how colleges run matrixes against other students and how race is used as a determiner. I’m not sure if the writers of the article looked at other evidence but the article only points to Asian Admissions at Harvard, quite literally one of the best schools. What the article fails to note is that affirmative action or race points are the biggest hurdle for Asians not applying to ivies. While the top scoring Asians apply to Ivies, it has been well documented how lower to mid scoring Asians applying to a decent but not excellent school from middle class families will lose their spot to an applicant with the same abilities but of a different race a majority of the times. In the article the idea of “race is used but is not a big determiner” is true in a vacuum but when looking at how competitive all schools are now race is often what lets some candidates get admitted over others. While there is debate about whether AA is justified at the highest levels of education this article completely misses is how it hurts Asians everywhere else. While true that it is an opinions article, I couldn’t help but notice how it was advertised all around the school and could mislead many younger students into forming opinions about a highly controversial topic that would greatly affect others without knowing the full picture. There is nothing wrong with writing an article/opinion about affirmative action but the way it was executed is like a spit in the face for all of the people that I know that have to overcome it as a hurdle. It could’ve been easily written about how there is systematic racism in college as a whole or how low income families aren’t given the resources to even compete in college admissions in the first place but this article pushes some people up while bringing others down.