‘I never got to say goodbye’

Realities of fostering: Gabriel Byrd’s experience

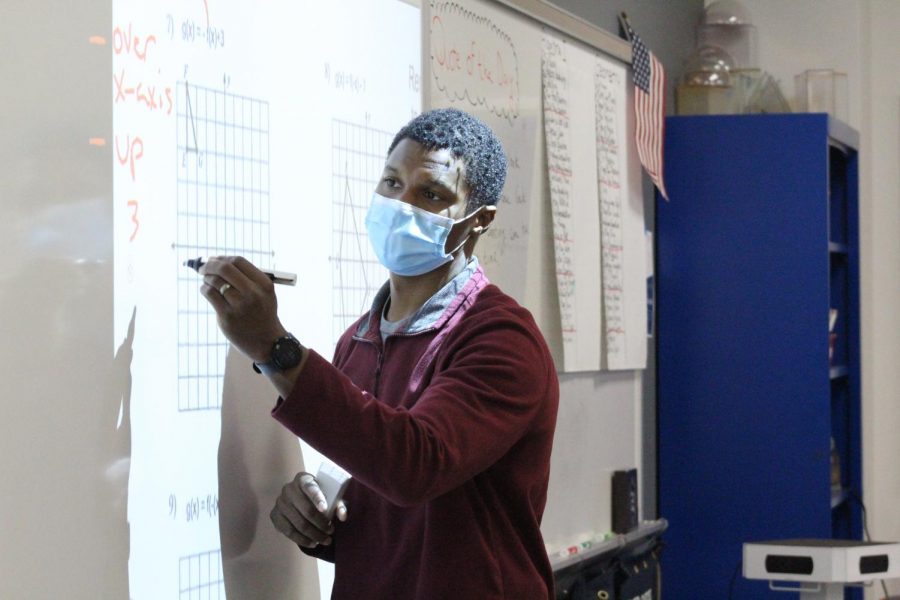

Geometry teacher Gabriel Byrd reviews homework problems with his 6th period students. Students describe Byrd as a caring and helpful teacher.

He grabs his keys and runs toward his car. He needs to get home as quickly as possible. All he wants to do is say goodbye to a child he and his wife had been fostering for three months. Thirty minutes later, he arrives at home, but he’s too late.

His wife shakes her head. Defeated, he heads to his bedroom and starts crying. He just learned that his infant foster son had been taken from him.

Gabriel Byrd and his wife Heidi Byrd were planning on adopting their first foster child, an infant. The foster agency assured them that the child had no family that would take him. However, that was incorrect, as a surprise family member stepped up to care for the child.

Geometry teacher, FCA and Spikeball Club sponsor, husband and father Gabriel Byrd has one biological son, 3-year-old Noah, and has fostered seven children with his wife.

“It’s easy to live in your little happy bubble and think the world is going great until you step out into those dark spots where kids are taken from their parents,” Byrd said. “We had the resources and the means to do it so [fostering] was our way of giving back and honoring God in the ways we could.”

Byrd said that he had his own experiences in Child Protective Services as a child, allowing him to empathize with those kids.

“It’s really bizarre to me that the government is…willing to give us money to take care of [these] kids when they can just [give] money to the parents to help take care of their kids,” Byrd said.“[If] they devoted some money to accountability and to helping out the parents, I think that’d be a better use.”

According to Byrd, taking children out of their home environment scars them.

“The impact that it has on children is so severe,” Byrd said. “That pattern [of changing environments] is going to devastate [them] to a point where [they] won’t be in a good spot.”

He recalls a recent experience with fostering a five-year-old boy from Liberty, Texas.

“He wouldn’t let it go [of his mom],” Byrd said. “He was crying and scratching [my] face because he just wanted to be with this mom so desperately.”

For Byrd, a big factor in deciding to foster was his faith.

“Not that I wouldn’t have done it [if I wasn’t Christian], but I wouldn’t have done it with the right perspective,” Byrd said. “I just want to give all that [I] can, helping kids get where they need to be.”

For Byrd, fostering hasn’t been an easy ride though. He experienced instances where kids would steal his personal belongings.

“I had my 18-year-old [foster child] steal $700 from me on two separate occasions, using manipulation and lies, and so that was really unfortunate,” Byrd said.

On top of that, he is often frustrated with the foster system, where on one occasion, the agency did not fully explain the extent of an autistic child’s needs.

However, despite the challenges, fostering children has been immensely rewarding to Byrd.

“I may not be able to see the fruits from any of the kids that [I ] fostered and I’m okay with that,” Byrd said. “Maybe [I’ve] planted the seed, [that] another person will water, and [eventually there will be] a flower that you didn’t get to see but you were a part of.”

Byrd has fostered newborns to 18-year-olds. He believes in the importance of opening his home to older kids as he claims they have a bad reputation in the foster system, leading to less people willing to open up their homes.

“Unfortunately, older kids do get a bad rap, so we wanted to make sure we went that direction with fostering,” Byrd said.

Whenever Byrd takes in a new child, he always takes the child shopping so they can pick out something they want. It has become a ritual for him to buy foster children new sheets every time they arrive at his home.

“You don’t know if those kids have had [the] opportunity to make decisions,” Byrd said. “Rather than just being handed things and saying, ‘This is yours’, we loved taking them to look at bed sheets [since] you gotta sleep with those.”

Mindful of the vast cultural backdrops of the kids he fosters, Byrd takes the time to learn about different cultures and incorporate them into his household. At school, his former and current students describe Byrd as a caring teacher who also takes their identities to heart.

“Mr. Byrd is really supportive and a great teacher to talk to if you need something,” sophomore Camille Lasics said.

Lasics isn’t the only student that has kind words to say about Byrd. Sophomore Erma Rosas also vouches for Byrd’s care toward students.

“Mr. Byrd is amazing,” said Rosas. “He really cares for his students.”

Byrd said his biggest takeaway from fostering is the perspective that he gained on life.

“It only takes a moment for you to go into a house like that [for] you [to] realize the severity of the need,” Byrd said. “If you could kind of get past your comfort [zone] you could be such a big light for kids who don’t have [homes].”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Bellaire High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Anna • Dec 8, 2021 at 12:00 pm

This is a great article! It was very interesting to hear what he had to say about the foster system. I also agree with a lot of what he had to say about it. This story really helps bring attention to the foster care system and Mr. Byrd is a great role model for anyone looking to foster. It is nice to have a teacher like Mr. Byrd at Bellaire. Also, I think the hook at the beginning was put together well and very impressive. The article itself was very well written so keep up the good work!

Carolyn • Dec 8, 2021 at 11:48 am

This was a really well written article. I didn’t know much about the foster care system and how harsh it really was. It piqued my interest to know more about how the government works. I think that there should be a better system than just taking kids out of their homes. While some families can’t provide for their kids Mr. Byrd makes a good point if the government can pay families to take in foster kids, why can’t they give money to families that need that support to raise their kids. Is there a better option to allow families to get more welfare or better opportunities to make money?

Haset Mekuria • Dec 8, 2021 at 11:40 am

I think it’s very kind of Mr. Byrd to foster children. Empathy is a very good trait to be present in teachers. The American Foster Care System is a very interesting, and I would like to learn more about them later on. There are more than 400,000 children in foster care today, but only around 200,000 foster homes (in terms of the USA). I hope that in the future foster kids and/or parents will get more of a say when foster children are adopted. Thank you to Mr. Byrd and the author of this article for sharing this story.

Meaghan • Dec 8, 2021 at 9:57 am

After reading this article, I have been so touched by Mr. Byrd’s compassion and kindness. It is truly heartwarming to hear that Mr. Byrd cares so much about these suffering children and that he dedicates so much of his time to greatly improve their lives. Even though he has experienced unfortunate events, such as thievery and lying, Mr. Byrd continues to foster and care for children no matter their background. It is extremely sad that he never got to say goodbye to his young foster son, but I hope in the future that he continues to foster more children in need of a home. Mr. Byrd is putting goodness into the world and inspiring others, like me, to do the same.

Grace • Dec 8, 2021 at 9:52 am

I really enjoyed reading this story. It is written very well, and I think it’s important that they showed the hard work and dedication it takes to foster kids. A lot of times people think of the rewards they will get out of raising kids, but they never think of the effort it takes to receive those rewards. I think it’s amazing how Mr. Byrd is willing and committed to putting in that work even if he doesn’t get to see how he helped that kid. Also, it’s great that he is opening up his home to kids of all ages and backgrounds. Great story!

marquesa madison • Dec 8, 2021 at 9:44 am

This article is a very clear example showing that teachers already busy with what they are doing with their students, assignments, and school itself, still make time to create a difference outside of the classroom and aside from education. It’s honestly very inspiring that a teacher would set aside time to make a whole person feel comfortable in an oftentimes stressful environment, while also having enough time for individual students and grading. Mr. Byrd is, not from my experience, a great teacher who gets to know his students other than just teaching and clearly shown in the article is overall a great person and teacher.

Jesse F • Dec 8, 2021 at 8:55 am

It is interesting how there are still people who are able to do these thing nowadays. Fostering a child may not be easy but it opens many opportunities to many kids (infants-18yr).I think its great that Mr. Byrd is doing this. I hope that when people see this they will do the same thing. Inspiring!

Paulette Ali • Dec 7, 2021 at 2:58 pm

Me and my friend Susan enjoyed this story at the Sugar Creek Baptist Church. We shared this story with the Youth Group. I think it is so important for the younger generation to have good Christian role models such as Mr. Byrd. This story is bringing light to the real struggles of the foster system. Thank you Mr. Byrd and may you have a blessed day.

Allenya Mooroir • Dec 7, 2021 at 1:37 pm

Great story! Very impressed with the hook in the beginning! Also awesome to see that people are still wearing masks in school!! Mask Up!! #spreadlovenotgerms.

Amy Green • Dec 7, 2021 at 1:13 pm

Wow! What a beautiful story! I am so glad we have such strong loving students willing to open their home to others! Keep up the great work Mr. Byrd!