Why my oma was Dutch and I am not

We were on the beach chasing our cousins’ three dogs when my cousin Simon asked why my oma, my grandmother, left the Netherlands.

The last time I saw my Dutch family, we were having a blast on our day trip to Scheveningen. Our departure the next morning left Simon wondering why we did not live nearby, and why our stays in the Netherlands were always temporary.

Why was my oma the sister to leave? I do not know the answer to Simon’s question, but I do know that our grandmothers had very different childhoods.

Born in Surabaya, Indonesia on April 30, 1934, to Dutch parents stationed in the country, Margaretha “Maggie” Hillenius peacefully experienced the first two years of life alongside her older brother. Their mother, Klazina, exploited their proximity to the beach, often taking her little ones to let mild waves crash over their chubby infant legs.

Returning to the Netherlands in 1936 without her father, who had to stay in Indonesia to perform his duties to Queen Wilhelmina as the second-in-command of the Dutch naval army, Maggie made her way back to a country neighboring one of expanding fascism.

As a non-Jew, Margaretha witnessed the cultivation of war that would quickly take away her neighbors and friends. I remember her saying she would think of better times in the peak of war. She would think of her father and the freedom she had to play with her schoolmates in the fields of Bussum.

Living on the outskirts of war in the house of her paternal grandparents in Bussum, she passed the lonely times playing the piano.

While doodling together (as my oma and I did a lot when I was little), my oma recalled the time she yelled an angry phrase to the Nazis lining her path to school. Her unabashed disrespect for the German occupiers should have killed her. Thankfully, they ignored the little Dutch girl and her little angry words.

At the time, the Nazi soldiers posed little threat to her non-Jewish family. However, in the peak of war, from 1943-1944, her grandmother Wilhelmina decided that she could do more for her suffering neighbors and began hosting small Jewish families in her basement. They harbored one family and for only a few weeks at a time, but every Nazi at the door had the potential to discover their operations and persecute the families and their accomplices.

There were no outside escapes from the anxieties at home. The bombers flying overhead and strict occupation rules were the reasons that her mother kept a strict curfew for her two children.

Her frequent opposition to my constant climbing and outdoor adventures as a child makes it difficult for me to imagine her as a little girl, not only breaking curfew, but venturing into German-owned land to scavenge for any small vegetable to bring home.

The lack of food met its peak in Hongerwinter (Hunger winter) when Germany cut off food and fuel shipments from farming towns. Hongerwinter lasted until liberation and hailed 18,000 deaths. There were few sources of food for the Hillenius family, and despite the supply deliveries by the Royal Air Force, Canada, and the United States, there were many nights without dinner and, in the worst periods, entire days without food.

Desperate times were chaotic, and my oma described the civil unrest and her close encounter with kidnapping. When she was 10 years old, riding her bicycle down a sunny path, a man

jumped out of the bushes and tried to grab her. She barely escaped by kicking him and pedaling away.

After five years, in 1945, it was time for Maggie to reunite with her father. One spring afternoon, she was called from school to watch the procession of returning naval officers, one of whom was her father.

On Maggie’s 11th birthday, April 30, 1945, which her father was there to celebrate, Hitler died by suicide. The genocide was finally coming to an end.

Unfortunately for Maggie, that same year, Johannes was called back to Indonesia, this time, taking his wife with him. In 1946, Marjolein, Simon’s oma, was born, and in 1949, Marijke, the youngest sister was born. This meant that Joop (Maggie’s brother) and Maggie would be left again, this time under a new arrangement: Maggie would move in with her childless great-aunts, and her brother would remain with the paternal grandparents. Maggie’s parents returned to the Netherlands several times to visit before finally settling back in the Netherlands in 1950.

At 18 years old, Maggie was up and away, becoming an au pair in England and later in France. Her favorite place seemed to be Beirut, Lebanon. Had she decided to marry her Lebanese boyfriend, she may have settled there.

My mother used to say that my oma would have found a way out of the Netherlands, one way or the other.

By the time of her American naturalization, Maggie was more isolated than ever from her culture. With few to speak to in Dutch, she spoke her native tongue less frequently.

It was her duty to raise her nuclear family alone around the world, even if that meant sacrificing her home. Nevertheless, she was not the first to make sacrifices in her family. The legacies of the women in her family left the internalized expectation to be a “sterke vrouw” (strong woman). Her mother married a literal white glove on her wedding day, taking photos with a stand-in man because her military husband could not attend their wedding. In Maggie’s childhood, she observed her grandmother hide Jewish families, having to confront snooping Nazi soldiers. Subsequently, it was her turn to sacrifice for the betterment of her family.

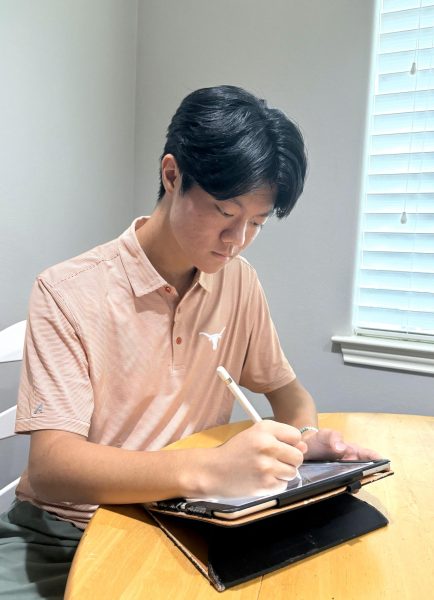

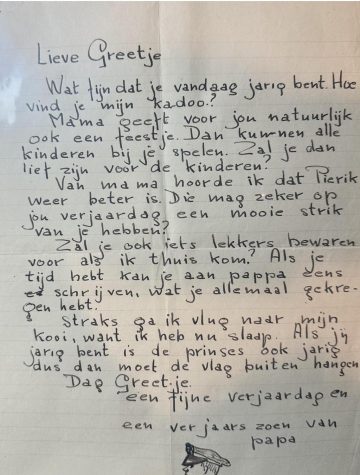

As her father wrote to her during the war, she maintained contact with loved ones and friends in her adult life by exchanging letters.

Her death in 2019 left many questions unanswered. Since then, I have enjoyed trying to piece together the gaps in my knowledge of her life. I will never know the full story, but knowing more about her childhood explains her sacrifices and why there is an ocean between my Dutch family and me.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Bellaire High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.