Modern art gets too much hate

Why does modern art get so much hate? Modern art may seem meaningless at first glance, but when you consider the context in which the art is created, you may uncover the significance.

“I could’ve done that.”

“How is that art?”

These are the statements that have been relentlessly thrown at modern art from the very beginning of its conception. And it is since this conception that modern art has drawn criticism from viewers as elitist, childish, and unqualified to even be considered “art.”

“How could Pollock’s splatterings of paint ever be considered an American masterpiece?”

“Who could ever enjoy Reyman’s all-white canvas paintings?”

Those are some common critiques I hear about modern art. While paint splatters and white canvases aren’t what we expect when we hear the term ‘art,’ the artists that created those pieces intentionally went past the norm to push the boundaries of art..

Beginning in the 1950s and 1960s, contemporary abstract art began entering the art market. These new artists like Frank Stella, Tony Smith and Sol LeWitt worked to remove emotion, and strip their art of distinctive features.

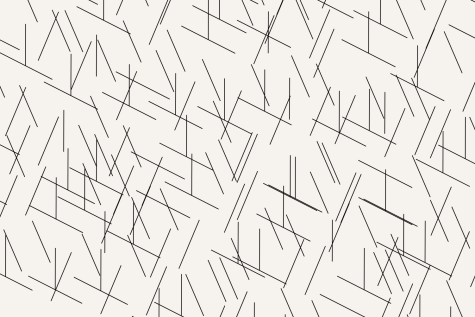

Abstract modern art featured basic shapes, repetition and new materials. Forms were repeated on the page and they did not have to follow conventional compositions. The artist no longer sat with a miniscule paintbrush behind the canvas, microscopically adding detail in every highlight, shadow, and crease.

Instead, the artist experimented with new mediums and ideas. Tony Smith played with steel to create his large geometric sculptures. Anselm Kiefer incorporated ash, straw, lead and shellac into his paintings.

Their abstraction was a radical rejection of the art that had come before.

For centuries, art was about achieving mastery of the craft. Artists trained for years to fool the audience into believing that a hand-sculpted marble statue was more than just a glorified rock.

However, modern art opposes this notion.

This leads to works such as the wall drawings of Sol LeWitt. You might stare at his black geometric lines and feel frustrated. Whereas connoisseurs of his art believe it to hold some sort of profound meaning that isn’t perceived by the average eye.

But what if there is no secret meaning?

Just like how you may appreciate an Edward Hopper painting for its technical skill, I can appreciate the works of LeWitt for their conceptual skill.

While it requires immense ability to realistically depict an object, I think abstracting an object from reality is even trickier.

Take an apple for instance.

In art class, I’ve learned various shading techniques, how to mix colors, and how to blend. So If you set an apple down in front of me and asked me to draw it from life, I would immediately know what to do.

On the other hand, if you had asked me to abstract the apple, I’d have to pause and ask myself how to approach the task.

What makes an apple an apple?

For me, the identifying characteristic of an apple is the crunch of the flesh when you bite into one.

In that case, I might abstract the apple into jagged lines on the page. The final product may not be recognizable as an apple anymore, but that does not mean the art requires less skill than a realistic depiction. I had to use skills of conceptualization and reduction to portray what an apple is to me.

In traditional art, you can often derive meaning and appreciation for the work just by looking at it.

For example, if there’s a dove in a painting, that may symbolize the death of a loved one, which elicits an emotional response in the viewer.

However, with minimalist art, the meaning may not be apparent just by looking at it, but it emerges when you understand the context that surrounds it.

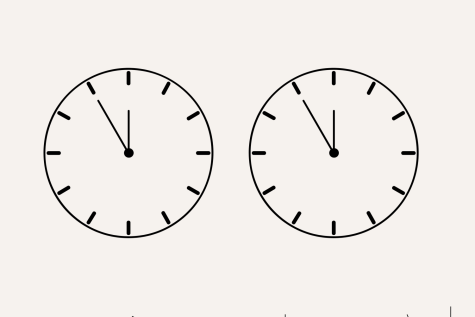

My favorite piece of art is Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s work, “Untitled (Perfect Lovers)” from 1991. At first glance, the work is almost comically simple. It’s two mass-produced, generic clocks hanging on the wall with their times synchronized.

If you only look at the clocks themselves, the work seems to lack any meaning. Anyone can go to Target and buy two clocks to hang on the wall.

However, when you start considering the context in which the art was created, the work begins to take on deep emotional meaning.Because nothing, regardless of what you may think, exists in a vacuum of solidarity and isolation. Understanding current events and the artist’s experiences are essential to amplify your relationship with the work.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres was an openly gay man in the nineties. “Untitled (Perfect Lovers)” was created after his lover, Ross Laycock, was diagnosed with AIDS. The title, “Perfect Lovers” asks the viewer to consider the clocks as lovers, with the ticking of clocks as the beating of hearts. Clocks will inevitably fall out of sync with time, but the title suggests that lovers will remain perfect, even when they fall out of sync.

If you were only observing the two clocks, it would be easy to brush off his work, along with the work of other conceptual contemporary artists, as meaningless. However, taken in context, Gonzales-Torres’s work becomes a melancholy, yet hopeful statement in the midst of the AIDS epidemic in America.

While it is true that such art does not require a copious amount of technical skill, it does still require the artist to be a master of a whole another skill set. Abstraction, conceptual thought and exploration all do still require skill, but a different form of it.

Just as we value various types of labor in society–line cooks, surgeons, bankers–we also need to appreciate work by artists displaying different sets of skills.

So what if after reading this, you still don’t like modern art?

Well, instead of saying “I could do that,” or “a child could’ve done that,” in reaction to modern art, consider why you don’t enjoy it.

When people say something along those lines, what they’re trying to communicate is that the art does not display the technical skill they look for in art. It’s perfectly normal to have preferences, and there is nothing wrong with preferring art that displays high technical skill.

But it is important to acknowledge the artists who pioneered new approaches to material, purposefully avoided displaying technical skill, and undermined the art culture to expand our views of what is considered art.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Bellaire High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Hannah • Dec 15, 2022 at 1:58 pm

i think art is subjective, so as long as it makes you feel something, its art