An isolated experience: the low-point of my life

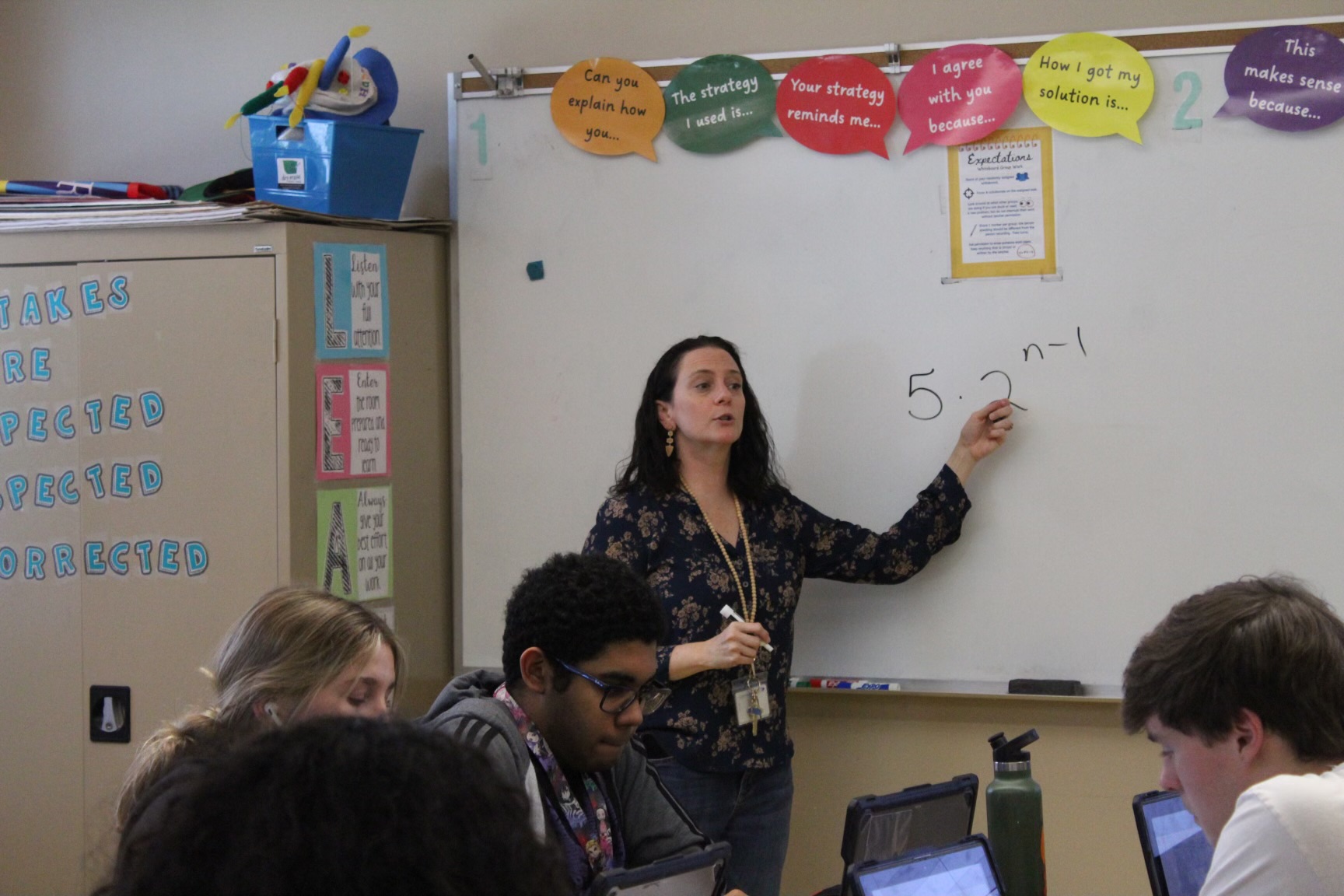

Panicker looks out the window from his hospital bed. He hopes that today will be the day that he gets to go outside.

Nov 6, 2020

The answer was always the same.

It did not matter what I asked for, nor did it matter what I felt. If what I wanted meant that I would have to step outside the four walls that my family lived in, then the answer would always be the same.

Only one word would escape my parents’ mouths, no matter the request, no matter the condition.

“No.”

The fear of seeing your only child laying sick and bedridden on a hospital bed is something that I do not know. What I do know is the unquenchable sense of craving. Craving for a chance to be outside once again, to go out and meet kids my age, to visit parks, to see my family mingle and laugh together with the world outside. I craved all of it, but all I had was a cold sense of guilt and desire. I saw cars zip by, helicopters land and take off, families make fun of each other, giggling and poking each other as they walked down the pathway. I saw all of it from my small hospital window, nine floors above the ground.

But I was never part of it. Each day, I laid on that same hospital bed, watching the life below me. Each day, I would wait for the doctors to come by, hoping I would get to go home. Each and every day, I would wait, hoping that tomorrow it would be me and my family walking down the pathway. That is all I did for a whole year.

Watch. Crave. Hope.

On Feb. 17, 2018, I was admitted to MD Anderson Cancer Center’s pediatric ward after a leukemia relapse. For three months, I only saw my parents and nurses entering and leaving my little hospital room. The intense pain of chemotherapy and the incredible joy of hearing I was getting better was all I lived off of.

Until the day finally came. June 6, 2018, the day of my bone marrow transplant.

One month later, everything was going better than expected. The doctors came by regularly to check up. The physician in charge asked me how I was feeling while his four assistants stood by him — taking notes. He took my vitals, listened to my lungs, gave me a huge smile, and finally said the words I had desperately been waiting to hear.

“Well, when do you wanna be discharged?”

It took a while to register, even more so for my parents. I cannot remember much after that. There was a lot of crying, a lot of “thank you’s” and more than anything, there were a lot of laughs. The joy my family and I felt at that moment was beyond anything I had ever experienced. Little did I know that joy would be short-lived.

I was always a timid boy. I still am to this day, but I would never consider myself paranoid. I like talking to people and being social in general; that is part of the reason I wanted to be out of the hospital. But the moment I returned home, those interactions were taken from me. It was not me who felt paranoid. It was my parents.

Could I blame them for feeling this way? Probably not, but I really wanted to. I could not stand staying at home while life continued outside without me. I wanted to be part of it, but my parents would not let me. They felt insecure at the thought of me stepping outside, worried about the consequences of me catching a cold or spiking a fever, terrified at the thought of seeing me back on a hospital bed. They were responsible for me, and they cared for me. They were aware of this fact. The problem was that they were too aware.

It had been two months since I had returned home, but nothing had changed. No dinner outside. No going to school. No talking to other people.

Nothing.

It stayed like this for the rest of the year. During my entire eighth grade year, I was homeschooled, and the only people I saw were my mom and dad. It took a whole year for the doctors to convince my parents to change their minds. They kept postponing sending me to school until they could not anymore.

They started to notice my implacable desire for being around others. It was getting out of hand. For a whole year, I had not seen anyone besides them. I think I almost started to resent them for not letting me see anyone. They knew things had to change, and they could not keep making excuses forever. And so finally, after a whole year of pestering, convincing, persuasion and me having angry tantrums, they let me attend Bellaire High School. I was overjoyed.

There was only one problem: I had become socially detached.

The first day was rough. Never before had I felt such anguish and distress walking up to my biology class in the science hallway. No one looked at me. Everyone was with their friends, chatting, giggling and just enjoying their day.

I felt out of place. No one even looked in my direction, but I felt like I was being judged by each and every one of them. The way I walked. The way I smiled. The way I breathed.

The way I looked. I felt all of it being judged.

It got better over time, though. I made friends, I got to know my teachers and I was even invited to my friends’ lunch table. But there was still that feeling of anguish. That itch in the back of my head, telling me that I was doing something wrong, demanding me to act better. I tried to ignore it, but I could not deny it.

It was not until the third month of school that I felt a little more in place. I felt like I fit in a bit more, I could talk more casually to people and even back-talk if needed. But that voice never left, it still hung on like a person clinging to the edge of a cliff, shouting at me from the edges of my brain. And it still got its point across.

Somedays, I would lose my appetite because of these thoughts, thinking about ways to look and act better. I never told my parents about this. Maybe that was a bit selfish of me, but I could not risk this causing my only chance to live like a regular teenager to be taken away.

I just could not.

It was not until the middle of the school year that something changed. It was the last day of the midterm exams. I wanted to leave a good impression on all of my teachers and friends so they would not forget me over the break. I wore a maroon T-shirt with a pair of extremely long and tight jeans. I combed my hair sideways and tried to keep it slightly curved to cover my bald spots. I put on a huge black and red fastrack watch and took a small breath of pride. Before leaving the house, I decided to take a final look at myself in the mirror.

And that’s when I saw him. A complete stranger stared back from the other side of the mirror. I wasn’t exactly shocked. I was confused.

This person standing in front of me looked good. I felt like he had a personality, tons of friends, maybe even a girlfriend. But what stood out the most, more than anything, was that he was putting on a show. He wore a façade, trying to trick himself into thinking that he isn’t a hopeful boy trying desperately to fit in, that he isn’t the kid who feels anxious at a grade below a 90, that he isn’t a kid who desperately wants people to talk to.

I cringed and felt revolted at the image of this stranger. Sure, he looked like he had his life set together, but that was all that there was to him. He simply looked like it. I hurried back to the wardrobe and put on my favorite blue T-shirt and a pair of comfortable jeans. I combed my hair normally, leaving my bald spots open to see, and put on a smaller blue watch. I took a sigh of relief.

I almost lost myself that day, nearly falling into the tantalizing belief that I could be someone else. Someone who had his life straight, someone who might have had a lot of friends, but also someone who would never be satisfied with himself, always striving for perfection. He would never be proud of who he was.

As I stepped out of the house that day, I felt a sense of acknowledgment. Acknowledge that I will never be perfect and that I will always have flaws. I will never be incredibly social. I will never have tons of friends. I will never have my life straight. I may never even look charming to anyone. And that’s okay.

Because I am a mess, and I am proud of it.